By Giovanni B. Ponzetto, a financial adviser with 32 years of experience based in Turin, Italy

Italy already was not in a particularly good fiscal situation pre-COVID, but it is in worse shape now. Giovanni B. Ponzetto takes a closer look at the financial challenges faced by Italy and its new Prime Minister, Mario Draghi.

Italy’s fiscal situation

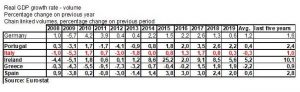

While Italian nominal growth was already much weaker than in comparable European countries – remember Italy was part of the so-called “PIIGS” -, the engine has been sputtering much more than nominal figures would suggest. This becomes evident when looking at real growth rates:

Apart from the official headline figures, the quality of how GDP is composed has also worsened over time (see here, page 14). The manufacturing component of GDP never recovered from its pre – 2008 levels, revealing a smaller ability of Italian industry to compete. Above all, it reveals how unattractive Italy has become as an investment destination. Italy attracts far less investment from outside the EU than Spain, for example.

Government forecasts for GDP range from -8% for 2020, to -12% according to IMF estimates, but that is a statistical figure that doesn’t account for a number of important factors: COVID disproportionately impacted Northern Italy, the economic engine of the country, and the Italian government has imposed a ban on firing employees, something which renders unemployment data almost useless. As a result, GDP figures should be treated with suspicion.

Moreover, public sector employment has increased, due to a hiring spree in the healthcare and education sectors. Those are accounted for as gross instead of net payments, and are calculated to contribute both to prima facie tax receipts and GDP, even if this really amounts to a zero sum game for the public sector. Even with such controversial measuring, the Italian debt to GDP ratio is projected to grow from 135% to 166%. Even ignoring that the public and quasi-public sector might contribute less than individuals and private entities to the state’s coffers, such an increase in debt will take generations to absorb.. That’s also assuming that the political will to bring debt under control would be found and that the ECB would continue to suppress the “spread”.

“Europe” is both a help and an obstacle in all of this. Yes, the EU’s “recovery fund” will be partly distributed as grants, but it is financed through debt issuance, which Italy, as an EU member state, will partly need to repay. Moreover, the EU will be giving clear directions as to which ways to invest the money to make the investment either “Halal” or “Haram”.

However, some of the things the EU considers as a permitted way of investing are not strictly “investments”, as they lower productivity instead of raising it: think of the “Green New Deal”, for example. Clear indications of how this would look like were given by EU Commission President Von der Leyen during her State of the Union address, and by project guidelines for the recovery fund submitted by the current Italian government to Italy’s Parliament. So, at the end of the exercise, Italy’s total public sector debt will be even higher, even if the cost for Italy to finance it will be lower, as there won’t be the “spread” premium.

Will Italy struggle to refinance its debt?

This question hinges to a very large extent on both European Central Bank and EU policy decisions. Italy has not been refinancing its debt at whatever a free market rate would be for over half a decade now. No one honestly knows where the market clearing price is, only that it would be costlier than it is at the moment. As a reminder, a simple “I am not here to control spreads” phrase by Mme. Lagarde last Spring was enough to cause Italian government bonds to suffer a heart attack, forcing her to water down her comments.

Italy’s financing needs are now higher than previously forecasted, both as a result of the need to refinance expiring debt and due to COVID expenses. A grand total of half a billion of bonds are due to expire in 2021-2022. On top of that, there will be the new financing needs.

What’s the role of the ECB?

So far, no Eurozone member state has struggled to issue debt, mostly because markets have been severely controlled, due to the ECB’s interventions: New issuance of German government debt has been yielding less than zero for some time now, something which in a rational world should cause concern, if not panic. One may wonder whether investors, certainly market “professionals”, do not know the basics of savings, and above all, of investment: rationally, one would only hand over cash if one is compensated for the additional risk. I may be old school but I was taught that what makes sense for the money manager should make sense for the client, but I struggle to see how commercial advertising saying “we lose your money better than anyone else!” would convince many.

However, as long as the music continues, this game of musical chairs will continue and ever increasing amounts of both Italian and European bond issuance will be turning into negative territory. Everyone is bitterly aware that, in case the music stops, having a more or less sizeable portfolio of Italian bonds, even if these still may have a positive yield, won’t be a good idea.

In a nutshell, no one who doesn’t raise an eyelid buying negatively yielding German bonds will care much about Italian refinancing risk. That’s not to say there is no such risk, but it is entirely political, dependent on Northern European willingness to support ECB policies and Southern European willingness to respect conditions linked to all of that.

Disclaimer: www.BrusselsReport.eu will under no circumstance be held legally responsible or liable for the content of any article appearing on the website, as only the author of an article is legally responsible for that, also in accordance with the terms of use.