By Gunther Schnabl, Professor of Economic Policy and International Economics at Leipzig University

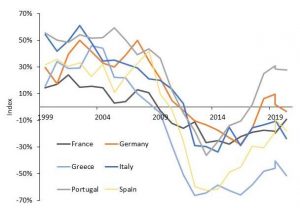

Last fall, the president of the European Central Bank (ECB), Christine Largarde, invited young Europeans on Twitter to contribute to the debate on the future of the euro. The reaction was harsh. Many of the responses contained the hashtag #bitcoin, revealing strong distrust towards the euro, the ECB and Christine Lagarde. This virtual event is an illustration of the general erosion of trust in the ECB, which did improve during the recovery between 2014 and 2019, but is still far below the level in 1999, while it deteriorated again during the current crisis (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Net Trust in the European Central Bank

Source: European Commission. The index is the ratio of respondents who answer to trust the respective institution minus the ratio of respondents who do not trust. 2020 data are preliminary.

The erosion of trust may result from three phenomena concerning ECB monetary policy.

First of all, perceived inflation is significantly higher than officially measured inflation.

Secondly, despite helping to stabilize growth in recessions, the ECB’s monetary policy has paralyzed growth, with a negative impact on real incomes as a result.

Thirdly, the ECB has caused harsh negative distribution effects.

- Perceived Inflation is Higher than Officially Measured Inflation

According to the European Commission, the perceived inflation rate in the Eurozone has been on average five percentage points higher than officially measured inflation (see Figure 2). During the current crisis, as prices of purchased goods (in particular food and beverages) increased, whereas prices of non-purchased goods (fuel and energy) declined, this gap has become even larger. The discrepancy may be due to a subjective perception of inflation, whereby people attach more importance to rising prices than to falling prices. A closer look at inflation measurement in the Eurozone reveals, however, three systematic distortions.

Figure 2: Officially Measured and Perceived Inflation in the Eurozone

Source: ECB and European Commission. Perceived inflation as mean.

First of all, prices measured in the stores are adjusted based on quality improvements: For instance, when computers have more power, cellphones have more features or refrigerators become more energy efficient, prices are reduced in the official statistics. In contrast, if quality is getting worse – for instance as service is reduced, life-cycles of products are shortened or the share of plastic components in products is increasing – prices are mostly not calculated upwards. That the dimension of this quality adjustment is not made public does not enhance trust either.

Secondly, although the prices of real estate have increased strongly in many regions of the Eurozone and have become unaffordable for an increasing number of people, owner-occupied housing is not part of the EU’s harmonized consumer price index (HICP). Instead, only rental prices – which are often subject to government controls – represent housing in inflation measurement. The weight of rental prices in the harmonized consumer basket is about 6% (!) and rental prices are subject to quality adjustment. Even more, stock and other asset prices – which have increased dramatically because of the ECB’s ultra-loose monetary policy – are not included into inflation measurement (Mersch 2020).

Thirdly, many governments and the EU have kept the cost of some goods – in particular food and health care – low through subsidies, financed by taxpayers. Although in this case prices have remained comparatively low (e.g. food) or are even not part of inflation measurement (e.g. public health care), consumers – in their capacity of taxpayers – still need to carry the cost. For instance, in Germany since euro introduction, taxes have increased on average by roughly 3% per year, far above the ECB’s (close to) 2% inflation target.

All this suggests that the loss of purchasing power suffered by European citizens is much larger than suggested by official HICP statistics.

- ECB monetary policy has hurt growth and real incomes

Because the officially measured inflation rate has remained low and because it hardly reacts to the ECB’s monetary policy decisions, the ECB has been able to gradually expand the scope of its powers (Stark et al. 2020). Whereas originally, the main goal of the ECB was to maintain price stability, since the European financial and debt crisis, the ECB has rescued Eurozone banks, the euro (“whatever it takes”) as well as highly indebted Eurozone governments. Under Christian Lagarde, also climate policy (#GreenECB), virus protection through a €1.850 billion Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme and gender equality (#EmpowerWomen) were added to the ECB’s shiny bouquet of goals.

With the growing responsibilities attributed by the ECB to itself, its balance sheet has expanded from 10% of Eurozone GDP to now more than 60% (Figure 3). This process is expected to continue and even accelerate. The budget of the ECB has grown on average by close to 10% per year since 1999, far above the 2% inflation target (Israel 2020) and also above wage growth in the Eurozone.

Figure 3: ECB Balance Sheet as Percent of GDP

Source: ECB and IMF. 2020 own calculation based on the assumption of a nominal growth rate of -5% in Japan, -5.3% in US, -7.3% in the Eurozone.

While all these measures may help make the world better, in the medium term, they have a negative impact on growth, as a growing number of Eurozone enterprises is “zombified”. The ECB has cut short-term interest rates from 4.75% in May 2001 to now 0% and has nudged the long-term interest rate close to or even below zero. Since 2015, large Eurozone enterprises are profiting from the Corporate Sector Purchase Programme, which not only significantly reduced the interest rate burdens, but also – in combination with the Public Sector Purchase Programme – provided large-scale windfall profits to export-oriented enterprises, as it caused the euro to depreciate.

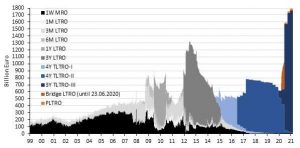

Since 2014, the ECB’s “targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs)”, which are ECB loans to banks with a favorable interest rate, amounting to close to 1800 billion euros (Figure 4), ensure that generous credit provided by the ECB to commercial banks is being passed on to enterprises. Given that the interest rate of TLTRO credit has declined to -1% percent, this represents an explicit – and not democratically approved – subsidy, in particular for highly-indebted enterprises.

Figure 4: ECB Longer-term Refinancing Operations.

Source: Schnabl and Sonnenberg (2020).

Continuously falling interest rates did not only have a deflationary impact on prices (thereby helping to keep inflation low), they have also resulted in less strong incentives for enterprises to increase efficiency and to innovate. As a result, a rising number of “zombie enterprises” with low returns is now dependent on loans that do not carry adequate risk pricing (see also Banerjee and Hofmann 2020). At the same time, this has stimulated commercial banks to extend de facto non-performing loans, in order to avoid damage to their balance sheets. The result is that productivity growth in the Eurozone has trended towards zero and is likely to have become negative during the current crisis.

Because productivity growth is the basis for real wage growth, wages have come under pressure. This process has accelerated in the southern Eurozone in the wake of the European financial and debt crisis and is likely to be extended to the northern Eurozone from now onwards. The public perception of the decline of real wages would be different if higher inflation would become visible in inflation statistics. As contributions to social security systems can be expected to decline due to depressed wages, welfare systems in Europe will become even more become dependent on state subsidies, which will need to be financed with higher taxes and/or – like in Japan – with government debt financed by the central bank.

- The ECB has caused large-scale and unfair redistribution of wealth

The ECB’s ultra-loose monetary conditions have pushed up stock and real estate prices and will continue to do so, while they cause real wages to decline and the real returns of savings on saving accounts continue to be negative. While rich people in Europe tend to hold larger shares of stock and real estate, and Europe’s middle classes tend to keep their savings on saving accounts, wealth inequality will continue to grow.

This process is accompanied by a redistribution from the young to the older generations, as stocks and real estate are overwhelmingly held by the latter. Due to the negative effects of the ECB`s rescue policies on productivity, the wages of young people entering the labor market will continue to decline in comparison with former generations. For the young, the units of labor required to purchase their own home, will therefore continue to increase. In countries with rigid labor markets, in particular in southern Europe, youth unemployment is expected to remain high or even increase further, as the ECB’s monetary policy paralyzes growth.

Last but not least, the ECB’s persistently low interest rates have a redistributional effect of favoring large enterprises, given how they profit more from the ECB’s corporate bond purchases and – due to their higher export-orientation – also more from euro depreciation than smaller enterprises do. Therefore, southern Eurozone countries, where economic structures are dominated by small and medium enterprises, are likely to suffer more from the ECB’s rescue policy than the ones in the north. In addition, the travel restrictions linked to the corona measures will continue to hit the southern Eurozone countries, that are more dependent on tourism, hard. At the same time, due to their membership of the euro these countries lack the possibility to adjust their competitiveness via currency depreciations (Mayer and Schnabl 2020).

This will all contribute to the pressure to more Eurozone transfers from the north to the south. Whatever the redistribution channel is – EU agricultural and regional policy, the structure of ECB government bond purchases, jointly issued EU debt, the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) or the “TARGET2” payments system of the European System of Central Banks – it has to be kept in mind that the euro and the persistently loose monetary policy of the ECB have transformed the economic environment for this redistribution process (Müller and Schnabl 2019).

Before the introduction of the euro, the German mark and other northern European currencies were under persistent appreciation pressure, because southern European countries continued to depreciate their currencies to boost their competitiveness. This forced northern European enterprises to continuously increase their competitiveness. In the north, the resulting productivity gains could be used to increase real wages, expand social security protection and finance transfers to Southern Europe. As the incomes of all Europeans improved, the acceptance of the European integration process was high.

With these productivity gains having faded away because of the increasingly loose monetary policy of the ECB, solidarity within the European (Monetary) Union is becoming more and more a “zero-sum game”. All euros being transferred from the north to the south of the Eurozone have to be financed by a growing tax burden or declining real wages in the northern countries. This process is likely to contribute to political destabilization, as the burdens for the younger generations can be assumed to significantly increase.

From this point of view, the recent 750 billion “Next Generation EU Fund”, which was announced as ‘a magnificent signal of solidarity and willingness to reform‘ (European Commission 2020) is unlikely to be a sustainable arrangement to avoid growing conflicts of interest within the European (Monetary) Union. Instead, a return to a stability-oriented monetary policy should be at the core of a reanimation plan for the old continent.

Disclaimer: www.BrusselsReport.eu will under no circumstance be held legally responsible or liable for the content of any article appearing on the website, as only the author of an article is legally responsible for that, also in accordance with the terms of use.