By Dan Kral, Europe Economist

When ECB President Christine Lagarde’s remarked in mid-March 2020 that “the ECB is not here to close spreads”, the spectre of another Eurozone sovereign debt crisis re-emerged. Yields on Eurozone periphery’s government debt shot up as the expected severe impact of COVID-19 on Eurozone economies and an aloof ECB caused panic in financial markets.

Two developments have stabilized Eurozone sovereign debt markets since.

First, there’s the ECB’s Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP), with a total envelope of EUR 750 billion. It was announced only a week after Lagarde’s infamous remark and was expanded to EUR 1.35 trillion in June and EUR 1.85 trillion in December (16.5% of Eurozone GDP in 2020). This effectively signalled that the ECB is indeed here to close the spreads.

Second, the historic agreement on a EUR 750 billion Recovery Instrument by EU27 leaders in July, dubbed “Next Generation EU”. This involved that for the first time, the EU Commission would issue debt jointly backed by EU member states, which will be distributed to governments in the form of grants and cheap loans. The associated debt burden will be on the EU’s and not on national balance sheets. As a result, by December 2020, yields on Italian sovereign debt were even lower than prior to COVID-19, although the economy suffered an unprecedented contraction and debt to GDP is set to match post-WW1 record of 160% of GDP.

However, both factors on which the current calm rests may face significant hurdles.

To set the context, major Eurozone economies were in a very poor state even prior to the outbreak of COVID-19.

The French economy already contracted in the last quarter of 2019, when Germany only narrowly avoided a technical recession – two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth.

Italy has been in a semi-permanent recession since 2009, with output at the end of 2019 down by 5% compared to its pre-financial crisis peak.

German industrial output has been contracting in each quarter since early 2018, which is the longest streak since early 1980s.

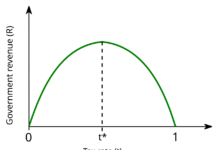

Government debt levels have remained stubbornly high and male prime-aged employment rates stubbornly low in some of the poorer Southern Eurozone economies (see Charts below). To respond to the deteriorating outlook, European governments were planning fiscal stimulus for 2020 anyway, while the ECB expanded its asset purchases in autumn 2019. On top of this came the pandemic, record contractions in economic output and war-style public deficits.

Will the ECB buy it all?

Following the expansion and extension of the PEPP at the June and December meetings, the ECB is currently set to make over EUR 2.2 trillion in net asset purchases in 2020-21 (through PEPP and its “regular” quantitative easing programmes). This means that the ECB will hoover up the vast majority of Eurozone governments’ net issuance in 2020 and 2021, meaning the largest creditor to Eurozone democracies is their central bank. Moreover, with re-investments of maturing principal currently set to continue until 2023, the pandemic emergency purchase programme is likely to run on for many years after the pandemic will have been over.

This shows that the ECB’s role in financing European governments absolutely dwarfs the bitterly fought-over Recovery Instrument. Investors continue to buy Italian government debt because there is a guaranteed buyer in the secondary markets.

In theory, under PEPP, the ECB is allowed to buy up huge quantities of Eurozone government debt without having to respect the same constraints on “issuer limits” it is required to follow with “regular” quantitative easing. These “issuer limits” determine the amounts the ECB is allowed to hold per issue and per issuer, as long as consumer price inflation doesn’t shoot up in a stagflation-like scenario, which is unlikely. As a result, PEPP disproportionately benefits the highly indebted southern member states. Practically, however, this may prove more challenging for a number of reasons.

First, it will be hard for the ECB to justify large scale purchases of government debt in the coming years, when economies return to normal, under a programme with the words “Pandemic” and “Emergency” in its name. Moreover, the flexible nature of the PEPP is unlikely to become a permanent feature of the ECB’s QE, as it would leave it exposed to legal challenges, while there is already opposition from key northern members of the Governing Council. The debate on recalibrating issuer limits and capital keys to reflect realities may therefore re-emerge with a vengeance.

Second, there is the inherent challenge for the ECB that it needs to conduct a “one size fits all” – monetary policy for a very diverse set of economies. Germany and the Netherlands have had much smaller recessions and will bounce back quickly, while Italy and Spain will likely experience the opposite. The ideal monetary policy for the two sets of economies would thus be very different. Certain members of the Governing Council may conclude that the relative underperformance of Southern economies results from underlying issues that can only be addressed through structural reforms, and that backstopping their sovereign debt markets is in fact counter-productive. In 2010, the ECB pushed Ireland into a troika programme before supporting its sovereign debt. Could this happen again?

A single remark in March by Christine Lagarde sent Eurozone sovereign markets into meltdown. The limits to the ECB’s actions and the different policy views within the Governing Council present much more serious structural risks to the outlook.

Recovery Instrument: what to do with the money?

The historic EUR 750 billion Recovery Instrument, agreed by EU27 leaders in July, is intended to fund productive investments and facilitate structural reforms across European economies to raise their longer-term growth potential and improve their fiscal position. However, the problem for the largest recipients is not that there is not enough money, but that, together with other sources of EU funds, there is too much.

From 2021 until 2027, during which the EU’s next multi-annual 1.000 billion euro budget is scheduled to be spent, EU member states are expected to “absorb” –i.e. “spend” – the following amounts:

- Unused structural funds from the 2014-20 EU multiannual budget, which in early 2020 amount to around EUR 140 billion, excluding national co-financing

- EU structural funds from the new 2021-27 multiannual budget, totalling 350 billion euro excluding national co-financing

- “Next Generation EU”, with 750 billion euro in grants and loans (even more in current prices)

Will certain member states be able to absorb up to 30-40% of their GDP in EU funding (excluding national co-financing) in the next few years and use that money effectively? The track record of EU spending is in that regard not encouraging. Even according to the European Commission’s hugely optimistic projections, Recovery Instrument grants will only flow in earnest in a few years time (Charts). In the meantime, eurozone governments will likely face large financing needs, due to continued fiscal support measures.

The process of disbursing Next Generation EU funds, which is very similar to structural funds, is likely to further constrain absorption. Governments are asked to come up with detailed reform plans on how to spend the cash, which will need to be approved by the Commission and the Council, with detailed milestones measured by quantifiable indicators and reimbursement long after the money has been spent.

There are many opportunities for this process to be delayed, assuming the Commission and member states can even agree on the reform plans in the first place, and for money to be wasted, absent a proper governance mechanism. The alternative of paying governments upfront was probably deemed too risky, given persistent corruption or issues relating to rule of law in some member states that are among the largest recipients in relative terms. For Italy and Spain, historically two of the worst absorbers of the EU’s structural funds, the new transfers are nice to have but are not game changers.

The Bottom line

Deep structural issues that were already evident prior to the pandemic have only worsened since, as the weakest Eurozone economies have also been hit the hardest. The expectation that from 2021, large amounts of EU cash will start flowing to member states’ treasuries, while the ECB will continue with de facto yield curve control, may prove to be misguided. A significant steepening of the yield curve in weaker member states once the emergency monetary support levels off resulting in spiralling debt servicing costs and fragmentation of the Eurozone, is a real risk. Many have written off the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), the Eurozone bailout fund with a total firepower of over EUR 400 billion, which can provide loans to Eurozone governments subject to them signing up to painful macroeconomic adjustment programs, as redundant and politically toxic. Time may prove otherwise.

Disclaimer: www.BrusselsReport.eu will under no circumstance be held legally responsible or liable for the content of any article appearing on the website, as only the author of an article is legally responsible for that, also in accordance with the terms of use.