In a series of articles, BrusselsReport.eu looks at how savers can protect themselves from monetary debasement. This article is merely summarizing possible strategies to follow and none of this should be taken as investment advice.

By Pieter Cleppe, editor-in-chief of BrusselsReport.eu

The first article in the BrusselsReport.eu series on “How to protect your savings from the ECB”, covered “buying stocks” as one possible option to protect one’s savings from the ECB. Hereunder, I’ll discuss a second possible option: buy physical gold.

Since the first article appeared, the European Central Bank has only doubled down on its policies to debase the euro in order to keep borrowing costs for deeply indebted Eurozone governments low.

My first article in this series stressed that buying stocks is a “rather risky investment option”, recalling the wise lesson of personal finance blogger Mike Piper:

“In a low-yield environment, there’s no way to get anything other than low expected returns without taking on significant risk”

Buying physical gold to protect one’s savings in today’s monetary environment may still be risky, but it probably is less risky than stocks, which in theory should mean that any returns will also less impressive. Any proper gold bug – a category to which I proudly belong – will stress that gold will not make you rich, it will only help you secure what you have, which is a more ambitious endeavour than assumed.

50 years ago this week, Nixon removed gold as the ultimate brake on the expansion of fiat money

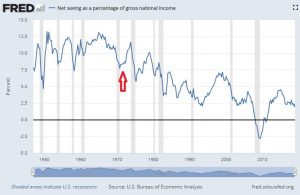

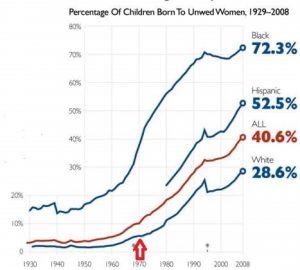

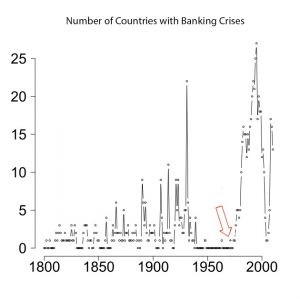

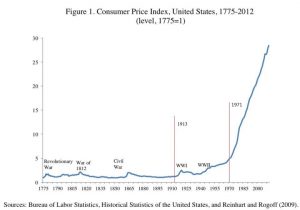

It is no coincidence that this article appears this week, given that 50 years ago, on August 15th 1971, U.S. President Richard Nixon announced his decision to close the gold window, suspending, with certain exceptions, the convertibility of the dollar into gold or other reserve assets, so foreign governments were no longer able to exchange their dollars for gold. Even if the “Bretton Woods” system that was broken up by Nixon was not a genuine gold standard, it did involve an ultimate brake on wild expansion of the monetary base by Central Banks and private banks. The negative effects of this decision on prices, wages and wealth can only be underestimated, and are well documented on https://wtfhappenedin1971.com/.

Why gold?

When deciding to buy gold to preserve value, it is important to understand why this precise metal historically emerged as a store of value.

At the end of the day, we only know that gold has been considered to be valuable for thousands of years. To understand why, remains guesswork.

More than 2500 years ago, the first gold coin currency was created, on the order of King Croesus of Lydia. Afterwards, gold as currency was adopted by Persia, the Greeks, the Romans, and afterwards. That was until 1661, when for the first time ever in Europe, the Swedish private bank Stockholms Banco issued so-called “Notes in bearer”, which were not fully covered by a metal deposit. The first use of paper money is recorded in China in the 7th century, where they called it “flying money”, given its tendency to lose value.

Marco Polo has described the ability of Kublai Khan, who conquered China in 1279, to have “made such a vast quantity of this money, which costs him nothing, that it must equal in amount all the treasure in the world.” Interestingly, according to Marco Polo, despite initial benefits, this was the end result:

“The best families in the empire were ruined, a new set of men came into the control of public affairs, and the country became the scene of internecine warfare and confusion.”

Consecutive European experiments with paper money were obviously warmly embraced by the authorities, as it enabled government funding and was much more practical than the old practice of having to reduce the percentage of real metal in coins, an art which was mastered by Roman Emperors, until Constantine would introduce the gold solidus (picture), a pure gold coin that became “the dollar of the middle ages.”

The Bank of England on its turn started issuing bank notes from 1694. Typically, paper money serves to finance things that are less than popular. This institution was established to finance another war against France.

In Scotland, a large-scale venture to colonise what is now Panama was financed with paper money, to a degree at least. This so-called “Darien scheme” was inspired by William Paterson, one of the founders of the Bank of England. The failure heavily damaged Scotland financially, according to some forcing it to accept a union with England in 1707.

This precedent did not prevent France from making a similar mistake. Under the guidance of Scottish monetary con man John Law, it set off to finance its colonization of Louisiana with a paper money scheme, having appointed Law as its Controller General of Finances. Law managed to convince the French government to let him open a bank, the “Banque Générale”, which could issue paper money, a novelty for France.

As could be expected, the bank issued an excessive amount of bank notes, which had meanwhile been made legal tender by the French State, culminating in the so-called “Mississippi Bubble”. Ultimately, Law and his cronies were forced to restrict conversion into gold, ending in a monthly French inflation rate of 23 percent in January 1720, culminating in economic disaster. Law had to flee the country and it would take another eighty years before France would again introduce paper money into its economy, by French Revolutionaries.

This was satirized by famous German playwright Goethe wrote “Faust”. Goethe himself served as finance minister of the duchy of Saxe-Weimar, from 1784, managing to convince ruler Duke Karl August not to experiment with paper money. Goethe proved to be right about the French revolutionaries. Their scheme of depreciated paper money, called “Assignats ”, eventually collapsed. As a General, Napoleon, who was visciously opposed to paper money, went against the Directory’s instructions to pay his army in Assignats. He instead paid them in coins, earning him loyalty. He also introduced the gold franc.

In 1729, French Enlightenment writer Voltaire had already warned that “paper money eventually returns to its intrinsic value – zero”, but later in history, governments have always been tempted to ignore this, from the American revolutionaries with their “Continentals” to 1923 Weimar , until 2007-2008 Zimbabwe and contemporary Venezuela , Turkey and Lebanon, bankrupting lives in the process.

Each week I publish Hanke’s #CurrencyWatchlist: a basket of rotten apples that have depreciated at least 20% against the USD since Jan. 2020. This week, #Lebanon is in the spotlight. The pound is junk, and inflation is sky-high. Lebanon desperately needs a currency board NOW. pic.twitter.com/x8VGVIpEVh

— Steve Hanke (@steve_hanke) August 8, 2021

Throughout all of this, owning physical gold would have been a good idea. Time and again, it has proven to be the method of choice for people to protect at least a part of their belongings.

Why gold then, and not something else? An article on the website of the “World Economic Forum”, which compares gold with all kinds of other chemical elements and metals, may be on to something:

“Once the above elements are eliminated, there are only five precious metals left: platinum, palladium, rhodium, silver and gold. People have used silver as money, but it tarnishes over time. Rhodium and palladium are more recent discoveries, with limited historical uses.

Platinum and gold are the remaining elements. Platinum’s extremely high melting point would require a furnace of the Gods to melt back in ancient times, making it impractical. This leaves us with gold. It melts at a lower temperature and is malleable, making it easy to work with.

Gold does not dissipate into the atmosphere, it does not burst into flames, and it does not poison or irradiate the holder. It is rare enough to make it difficult to overproduce and malleable to mint into coins, bars, and bricks. Civilizations have consistently used gold as a material of value.”

What about surrogates of physical gold?

Certainly, throughout the ages, alternatives have existed for gold, with silver as the most notable. Silver may be more affordable, but its price is also more volatile, as it has higher industrial use.

Nowadays, one can also buy gold and silver digitally, for example through gold and silver ETFs . There however is a thriving literature on why it’s better to buy physical, from fears that ETFs may not hold the bullion they promise to counterparty risk, meaning the “possibility the other party in an agreement will default or fail to live up to their obligations.” Canadian gold bug Eric Sprott, once described as “one of the world’s premiere gold and silver investors”, has linked his reputation to funds that promise to actually possess 100% of the gold or silver they pretend to have.

Sprott has also pointed out that “a lot of people that might have otherwise gone to gold have gone to cryptos.” This is of course the case, but as I made clear in a previous article covering crypto, those investing in crypto should realise that the value of it as a store of value is dependent on the extent whether the authorities will permit it to survive.

A breakthrough of #Bitcoin as money would be important. Western welfare states are strongly dependent on low interest rates. When people no longer use state money, “monetary financing” is no longer possible.

The @ECB says #btc may in theory endanger its "monetary sovereignty".

— BrusselsReport.EU (@brussels_report) April 13, 2021

Given how important access to the – digital – printing presses is for government finances, one can be fairly certain that most governments will lean to ban or heavily restrict bitcoin and crypto altogether, reminiscent of the E-gold saga. U.S. legislation doing precisely this is being decided at this very moment.

“Bitcoin maximalists” have accused other crypto currencies of permitting security leaks that make them vulnerable to a government ban, something they maintain is less likely to happen with bitcoin. Even the greatest believer in bitcoin should admit that in any case, the jury is still out for bitcoin, while gold has proven itself to be useful as a store of value for thousands of years.

Practicalities: Bars or coins? How to store? What about gold mines?

A whole literature deals with questions on whether to buy gold bars – they tend to be cheaper, as “premiums” are lower – or coins – they are probably more useful as means of payment.

Similar challenges arise on how to store gold: “bank holidays” can certainly given the experience of much more severe Covid restrictions no longer be ruled out as unlikely remnants of the past, so as a result, storing gold in a bank vault may be risky. On the other hand, storing gold at home may not be a good idea either, given the risk of burglary. Services offering storage of gold abroad have existed for a long time now, but the Covid crisis, with its many travel restrictions, should surely cause some reflection over this.

Gold investors typically recommend to invest in gold mines – or silver mines – as well, as the prices of such gold mine stocks tend to increase more than the price of gold – with prices also dropping more than the gold price itself. Here, a lot of caution is necessary, while a good stock picker may be even harder to find than for normal stocks.

Without issuing a recommendation, I’d like to mention one successful example. The Belgian “Analyse” newsletter – in Dutch – exists since 1981 – and has always had a great focus on picking gold mining stocks, with its “model portfolio” securing an average annual return of 16 percent between 1999 and 2020.

What is the “return” of gold?

The point of gold is not to deliver a return, but to preserve the purchasing power of savings, but in today’s context of wild monetary experiments, gold investments tend to perform even better than stock portfolios. Between 2000 and 2020, until the Covid crisis – which drove monetary policy to even crazier frontiers – gold did clearly outperform the U.S. S&P500 index, and that is during a period when great companies like Amazon, Google, Apple, Microsoft, Tesla and Paypal flourished:

Gold price in USD:

+400pct return from 2000- 2020 (500pct in EUR)

+300pct 2000-2009 (275pct in EUR)

+50pct 2009-2020 (200pct in EUR)S&P500:

+175pct return from 2000-2020

-50pct 2000-2009

+300pct 2009-2020(Rough estimates, but gold seems not such a terrible idea). #GOLD pic.twitter.com/9xt6IeUv1F

— Pieter Cleppe (@pietercleppe) March 28, 2020

On the other hand, looking at the period between 1990 to 2020, the price of gold increased by around 360% – in USD – while the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) gained 991%. Of course, the 1990s marked the real start of “globalization”, with the opening of the post-Soviet world and the continued opening of China, combined with the penetration of the internet.

Some have compiled the gold/S&P500 ratio, claiming that as “the ratio has fallen dramatically since 2011”, this is “suggesting a relative undervaluation of gold.”

This chart plots the gold/S&P500 ratio.

Despite significant disruption to the real economy due to COVID, exuberance in the stock market has continued unabated.

We can see that the ratio has fallen dramatically since 2011, suggesting a relative undervaluation of gold. pic.twitter.com/LhEeCJ9OO5

— In Gold We Trust (@IGWTreport) July 29, 2021

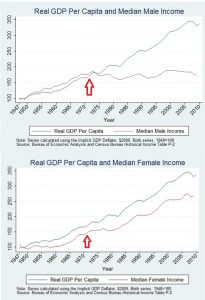

One must be cautious, however. Following the end of Bretton Woods in 1971, U.S. stocks (the S&P500 index) performed a rather meagre average annual 4.7% return between 1972 and 1979, compared to an annual average 38.1% return for gold during that period. Due to the average 8% inflation rate, that meant gold investors saw their purchasing power increasing with 609% as stock investors would lose 23% of their purchasing power.

After Fed chair Paul Volcker had been allowed to hike interest rates in 1979, the party was over for gold, and for 20 years. During the 1980s and 1990s, stocks – the S&P500 index – provided a 17% and 18.1% average annual return respectively, while investing in gold would see negative annual average returns of 2.8% in the 1980s and -4% in the 1990s. This means that, adjusted for inflation, investing in gold in 1980 would have made one’s purchasing power drop 54% during the 1980s and 50% during the 1990s. Of course, a caveat here is that one would need to have converted all of one’s savings into gold while going “all in” at the very peak of the gold price, which amounted to $594.90 in 1980. Furthermore, the idea that official CPI statistics are an accurate measuring of inflation must also be questioned.

One could make a case that if a new Volcker would be about to come along right now, in 2021, it wouldn’t be the best timing to go “all in” for gold, but for now, the leading Central Banks of the world are very much on the “when in trouble, double” path.

How much gold should I buy as a percentage of my belongings?

Someone’s belongings need to be separated into four categories:

- Cash: government-sanctioned money, which can be printed at will by Central Banks and is therefore highly vulnerable to depreciation of value. As explained in the first article of this series, “for savings that one cannot miss, there is unfortunately no other way than to simply pay the “inflation tax””.

- Company shares (stocks). This option is the focus of that first article. Historically, the average stock market has delivered 10% annually before inflation. Finding good stock pickers that beat the market is not easy, but there are examples.

- Physical gold and potential surrogates discussed in this article (physical silver, gold and silver ETFs, gold and silver mines, bitcoin, other crypto currencies)

- Real estate. This will be covered in the third article of this series, also comparing its performance to stocks.

Indian fund manager Vikas Gupta suggest the following advice, which is quite typical:

“Someone with stable and regular income should not put more than 2-5 percent of their portfolios in [gold]. And for those who do not have regular income, he suggests that they put in not more than 10 percent.”

This is not so different from well-known American gold proponent Peter Schiff, who has always recommended holding 10 to 20% of an investment portfolio in physical precious metals, adding that “defensive investors prefer to stick with the more conservative 2:1 allocation of gold to silver”.

Conclusion:

Gold will not make one rich, but it will help to secure one’s belongings, which is already quite ambitious in an uncertain world with great monetary experiments.