A book review by Jean-Paul Oury

“Our forests are burning” was the phrase used by French President Macron to announce the “One Planet summit” in France. Climate alarmism is now being imposed on everyone’s mind. And apart from a few sceptics, few dare to question the prevailing catastrophism.

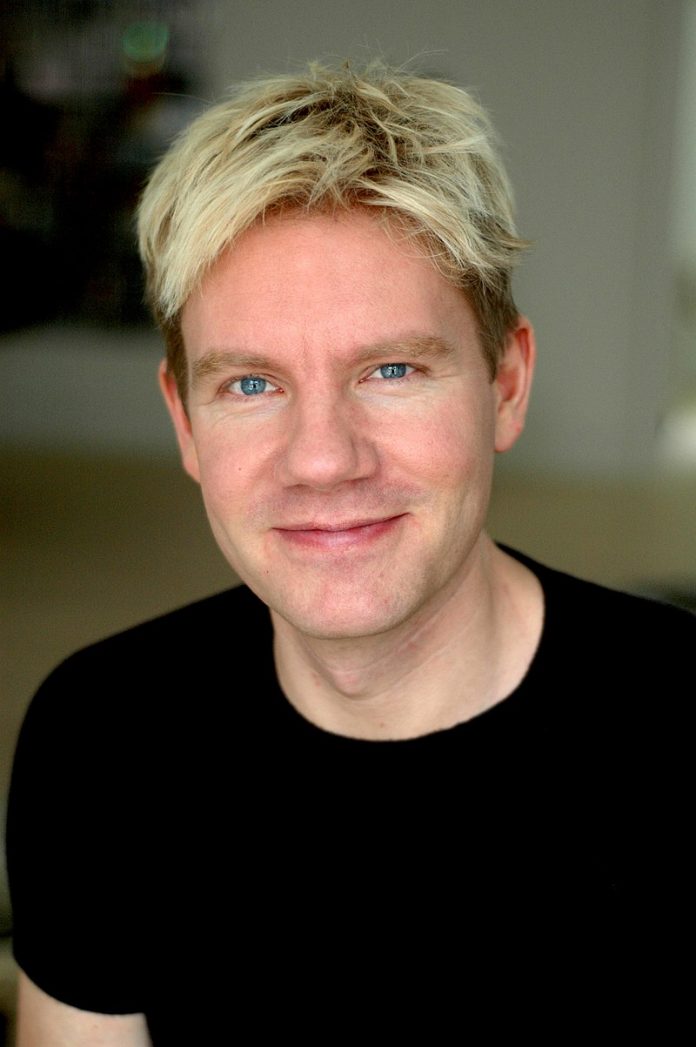

Nevertheless, this is the angle chosen by an ecologist who, paradoxically, has become famous for his scepticism. In 2004 already, Danish academic Bjorn Lomborg was denouncing the manipulation of ecologism on topics like global warming, overpopulation, depletion of energy resources, deforestation, extinction of species and water shortages.

Since then, a lot of water has flown under the bridge and this former Greenpeace activist, whom I could undoubtedly have added to my list of “converted environmentalists”, listed in my own recent book on the topic, has written a book, published last year, with the title “False Alarm. How Climate Change Panic Costs Us Trillions, Hurts the Poor, and Fails to Fix the Planet”, which throws a stone into the garden of the prophets of doom, or rather a bucket of water on the wildfire of climate catastrophism.

That’s the message conveyed by “False Alarm”, a formidable work, especially since Lomborg, as a statistician, never takes a political and/or ideological stand, but simply puts forward figures which he compares with each other, thereby relying on the theses of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the Nobel Prize winner in economics, William Nordhaus.

The book is divided into five main sections: a general introduction depicting the climate of fear that has taken hold, followed by a factual analysis of the truth about climate change, and then two “practical” parts: the first, which sets out what Lomborg considers to be false solutions, and the second on the real routes to follow. The fifth section is a general conclusion on how to make the world a better place.

The origins of climate terror

Lomborg begins with a startling statement: a survey of 28 countries around the world shows that half the population believes that global warming will lead to the extinction of the human race. He notes that the consequences of climate alarmism on the masses are really taking their toll, with parents no longer wanting to have children or children being reluctant to go to school, given how hopeless things are – between the lines, it’s clear that Greta Thunberg is being targeted, even though she is not mentioned. For him, there’s no doubt of the important role played by the media in all of this.

From the outset, the author makes it clear where he stands on these issues: he has been involved in the global warming debate for more than 20 years now, since the publication of “The Skeptical Environmentalist”, and for all of that time, he has argued that global warming is a real problem. He notes however that the discourse on this subject is becoming more catastrophic every day, as the rhetoric is increasingly extreme and less grounded in science.

According to him, science shows us that the fear of a climate apocalypse is unfounded. For example, when we read that we only have a few years left to act, this is not what science tells us, but what politicians tell us. This kind of statements come from politicians asking scientists what to do to achieve an almost impossible target. Lomborg uses a striking analogy: if scientists were asked what action to take to achieve zero car accident deaths, the answer might be to limit the speed to 5 km/h. In fact, science does not tell us here that we should drive at this speed, but that if we do not want to have deaths in car accidents, we should limit the speed to 5 km/h.

The first question which the author addresses is why we have so much difficulty in understanding climate theses. One of the main reasons is the way the media treat all this information. The statistician provides several examples to illustrate this.

The first and most striking example is the front page of Time Magazine featuring UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres, photographed in a suit with water up to his calves on the coast of Tuvalu, a small island in the Pacific, with the headline ‘Our sinking planet’.

Lomborg points out that if the media had done their job properly, they would have read the study published in Nature on the consequences of rising sea levels in this part of the world, which makes clear that things were slightly more complex: yes, global warming causes the oceans to rise, but Tuvalu has doubled in size. While over the past four decades, the water have risen, at the same time another accretion phenomenon is causing waves to bring additional sand to the beaches, due to the erosion of old coral reefs. The 2018 Nature study demonstrates that the accretion reinforces the erosion, thereby gaining land area. It concludes that the island in question can remain a living space for the next century. Nevertheless, the angle the magazine picked was: “our sinking planet”.

Politicians are not innocent here

The book cites a number of other examples that help us understand why the way information is processed plays a fundamental role. However, the media are far from being the only ones responsible. Politicians also play a considerable role. Indeed, for them, it has become a vehicle to make electoral promises in the following style: “I will save you from the end of the world, and my opponents will not”.

Another important factor are “ultimatums”. One of the most famous one is probably the ultimatum pronounced by Prince Charles in 2019 that there were only 18 months left to fix the climate change problem. This habit was initiated by the “Club of Rome” and its “The Limits to Growth” report written in the 1970s, which, among other false predictions, announced the end of gold by 1979, and the end of many other raw materials, such as aluminium, copper, natural gas and oil by 2004. Each of these predictions turned out to be obviously wrong.

Adaptation

Another essential concern for Lomborg is that the authors of a report tend to not take into account the possibility of adaptation by people. As a result, in the absence of any adaptation, it can be estimated that by 2100, more than 187 million people could be victims of flooding. When taking into account the capacity of individuals to adapt, the forecast immediately drops to 15,000 victims. Lomborg notes: “For millennia, humans have adapted to nature, and with more welfare and more technology, this will become even easier in the future.”

Scary climate article tells you: children of the future will experience many more climate disasters

But they ignore adaptation and many of their models are just plain bad

Demand policy-relevant information, not just scareshttps://t.co/fi1b5COMJD, https://t.co/kJetO61F8J pic.twitter.com/MVREl3oYYX

— Bjorn Lomborg (@BjornLomborg) October 3, 2021

GDP vs CO2

Once this general picture has been established, the author proposes to look at the problem by focusing on two indicators: that of the presence of CO2 in the atmosphere and that of GDP. After devoting a few chapters to false points of view (e.g. the “bulls eye effect”, which leads us to believe that natural disasters become more violent every year, when in fact they strike a greater number of homes concentrated in the same place), the author goes on to discuss a number of exaggerated or one-sided points of view (as he stresses there is always a positive effect, e.g. the fact that CO2 in the atmosphere facilitates the growth of vegetation).

Lomberg then proceeds to ask the central question: “What will global warming cost us?” This is a key point in the book. Lomborg draws on the work of William Nordhaus, winner of the Nobel Prize in Economics for his work on global warming. Nordhaus’ most accurate estimate would be a loss of 2.6% of global GDP for a 4°C increase, if we do nothing.

Desperate attempts to limit CO2 emissions

The next question then is what to do about it? The first thing which comes to mind, of course, is that of individual actions… a solution quickly put aside by a caustic anecdote that deserves to be quoted in full.

On the BBC’s “Ethical Man” programme, a man recalled how he and his family had been reducing their CO2 emissions. He had insulated his house, sold his car, reduced his meat consumption, and had even looked into green burials (although no one died). In total, he had managed to reduce his emissions by 20%, at great personal and financial cost. The funny thing is, however, that he ended up undoing all of his efforts by taking his whole family to South America, thereby blowing all of his family’s CO2 savings.

Lomborg lists other desperate and sometimes “sacrificial” attempts to reduce CO2 emissions, such as vegetarianism, electric vehicles, giving up air travel, and no longer having children. While discussing all of these efforts, the author shows that each time, there is a “rebound effect”. For example, vegetarians spend the money they saved by not eating meat by acquiring other goods, which cancels out their effort.

On electric vehicles, he argues that even if we reach the target of 130 million electric vehicles on the road by 2030, as aspired by the International Energy Agency, this would only save 0.4% of global emissions by 2030.

When it comes to flights, Lomborg mentions that even if every one of the 4.5 billion passengers flying each year were to remain on the ground, and this were to continue until the year 2100, the increase in global temperatures would only be reduced by 0.027°C.

On no longer reproducing, Lomborg shows the absurdity of a “logic” leading us to believe that we are responsible for part of the carbon emissions of our children, but also of our grandchildren and great-grandchildren (which puts a terrible responsibility onto our prehistoric ancestors). He had fun making a little estimate: having a child could be offset by buying an $8100 permit from the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI, or ReGGIe)

In sum, Lomborg concludes that all of these actions are far from sufficient to address the climate issue.

The green revolution which fails to materialise

“Why the green revolution is not yet here” is a question related to the failure of renewable energies (especially solar and wind power), despite the $141 billion annually awarded to them in subsidies. Despite these colossal sums spent by rich countries (Lomborg does not forget to point out that it is totally impossible for poor countries), the return on investment remains ridiculous.

One of the strongest parts of the book is Lomborg’s critique of the Paris Agreement, which aims to limit global warming to less than 1.5°C. He notes that there is no agreement on how to achieve this. He notes that there has never been an assessment of the cost of this ambition, as it would be the most expensive agreement in human history, amounting to an estimated $1-2 trillion every year from 2030 onwards, if it were implemented. This is a huge effort for countries and would only reduce temperature increases by 0.027°C.

New Zealand volunteering

Lomborg looks at the case of New Zealand, the first country to announce the ambition to achieve carbon neutrality, and the first to fail in this. As part of the Paris agreements, the country committed itself to this goal by passing a law in 2019. A local think tank has calculated the cost of this commitment. To reach only 50% of this target, it would cost the country cost $19 billion each year. Over the whole century, the cost would be equivalent to $12,800 per year per New Zealander, in the best case. And for what result? If New Zealand would achieve its carbon neutrality target in 2050 and would stay there until the end of the century, it would contribute to limiting global warming by 0.0022°C. Lomborg comments, “New Zealand is about to spend at least $5 trillion on an impact that will be almost impossible to measure physically.”

Five IPCC scenarios

A key question is which path to follow, or more precisely which strategy to adopt. For this, Bjorn Lomborg uses five IPCC scenarios (regional rivalries, inequality, middle of the road, sustainable development, or fossil fuels). He considers and evaluates the pros and cons of these solutions.

Each of these paths estimates that each individual will be richer in 2100 than today. For example, in the “green” solution, the average person will be six times richer in 2100, compared to 2020 (with an average income of $106,000). With the fossil fuel solution, this average income is increased to $182,000 per year (10.4 times richer than today). In order to evaluate the climate impact of these two scenarios, Lomborg relies on the work of Nordhaus. The green solution leads to an increase of 3.22°C – an annual cost of $3000; the fossil fuel solution to an increase of 4.83°C – an annual cost of $11000. Once these costs have been deducted, we arrive at an annual income of $103,000 for the green solution and $172,000 for the fossil fuel solution.

So here a big choice needs to be made… Knowing that a more prosperous world is able to adapt more easily, it is not obvious that we should take the green solution. However, the promoters of the latter often advocate “degrowth”, which Lomborg points out would mean fewer resources for our health, education, and technology, adding: “Our continued progress in eradicating poverty would be halted. The world would be darker, less healthy, less educated and less technologically advanced.”

With current renewable technologies, achieving the vision of zero emissions would be so expensive that Gilets Jaunes riots are guaranteed everywhere long before the goal is reached.#COP26 needs to unleash innovation instead.

My 2 page essay:https://t.co/DQCPgqVDI7 pic.twitter.com/5a6Ck453jf

— Bjorn Lomborg (@BjornLomborg) November 2, 2021

Helping the poorest

To fully understand the author’s argument, one must refer to the struggle he has been waging as a humanitarian activist for years, which serves as the basis of his thinking and commitment. Climate policies carry an exorbitant cost for the poorest. Whether they live in rich countries, in Africa or in Asia.

He cites the example of Typhoon Haiyan, which hit the Philippines in Tacloban in 2013 and killed over 2,700 people, noting that from 1992 to 2013, economic progress tripled the GDP per person in the Philippines, and that if the focus had been more on reducing poverty, the GDP could even have quadrupled. This could have saved the lives of over 300 people. Climate policies would have saved zero. To put it even more bluntly, to choose climate policies over pro-growth policies does not lead to 0 results. It means that more people die a preventable death.

Lomborg’s figures are striking, and it is hard to understand why the world’s politicians don’t fall in line with his arguments that really are common sense. Given that there are over 650 million extremely poor people in the world today, it would cost an estimated one hundred billion per year to get them all out of this situation. This considerable sum seems ridiculous compared to the $2 trillion per year that we have decided to devote to the Paris agreements, especially since these colossal efforts will have very little effect.

Five concrete ways to fight climate change

In the last part of the book, Lomborg proposes five concrete ways to fight climate change.

The first solution that seems to make sense is a carbon tax. Although he considers this to be a good idea, he thinks that it would be complex to implement at the global level. The implementation of such a tax would need to be calibrated carefully: a tax that is too high can have devastating effects on the economy without having a considerable impact on the climate.

The second avenue is innovation, and in particular R&D. This seems obvious, but the author reminds us of a few truths: OECD countries have invested very little in R&D. He cites a few projects, such as Craig Venter’s genetically modified algae which absorb CO2 and make it possible to create oil, tidal energy, CO2 capture systems and new generation atomic reactors. A public research effort should be made so to triple global investment in R&D in the next five years, to reach $100 billion annually.

In an interview, Lomborg explains this idea well. In particular, he insists that if the money used to subsidise renewable energies were spent on R&D for new energy sources and technologies dedicated to the fight against global warming, we would inevitably have a greater impact.

The third avenue is probably the most obvious, but mentioned the least: adaptation. It is true that people can easily adapt to climate change on their own, but this is not enough. Sometimes public intervention is needed, such as better land registry management, to target flood-prone areas. Lomborg notes that most alarmists are completely unaware of people’s ability to adapt.

The fourth is geoengineering, a technology which could, if studies confirm it, eliminate a significant fraction of the predicted global warming and at a lower cost. Lomborg has been studying this with his think tank, the Copenhagen Consensus Center.

The last avenue is prosperity. Indeed, a prosperous society is still the best solution for humanity to face the challenge of global warming. This is an idea rarely mentioned by the climate actors, and yet defended by the Nobel Prize winner in Economics, Thomas Schelling, as early as 1992. A recent study carried out in Tanzania shows how the poorest were the most affected by the arid climate and the richest were better able to adapt.

Climate isn’t the most important thing

The final question Lomborg raises is: “if we want a better world, is climate policy the most important thing to focus on?” He stresses that while it is essential to conduct the right climate policies, countering climate change is only one of many important policy topics. Unfortunately, it has come to take precedence over all other topics. To make the world more prosperous is just as important.

Lomborg mentions research conducted by his Think Tank on the policies that deliver the best return on investment. He also provides a ranking of these policies. Furthermore, he notes the fight against global warming should not distract our attention from the other battles to be fought, such as promoting open markets and free enterprise, developing health policies, fighting malnutrition, supporting contraception, education and technological development. Yet it is the obsession with ‘scare stories’ about global warming that is driving us into bad decisions.

Lomborg’s book can only be called “refreshing”. If there is one thing “urgent”, it is to read it.

This article was originally published in French, by The European Scientist

Disclaimer: www.BrusselsReport.eu will under no circumstance be held legally responsible or liable for the content of any article appearing on the website, as only the author of an article is legally responsible for that, also in accordance with the terms of use.