By Dan Kral, Europe Economist

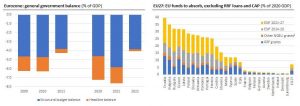

The recently unveiled draft budgets by eurozone governments reveal plans for bigger fiscal tightening next year than in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. However, whereas a decade ago, the eurozone almost fell apart as a result, there are several reasons why this time it’s different.

First, some of the tightening will be offset by spending related to the EU’s Recovery Fund and structural funds, which are accounted for outside the regular budget numbers.

Second, a decade ago, the global financial crisis soon morphed into the eurozone sovereign debt crisis, which led to a retrenchment in confidence and spending among both consumers and businesses, while the ECB tightened policy. In contrast, both consumers and businesses are now sitting on significant excess savings, confidence remains high, and the ECB is in no rush to hike interest rates or stop monetizing government debts.

Third, governments in Germany and France, which account for half of eurozone’s GDP, will almost certainly spend more than what has been planned for in their government budgets; in Germany’s case, to take advantage of suspended debt rules for green investment purposes, and in France’s case, to boost household incomes during an election year amid an energy price squeeze.

Some real gems in the recently released @EU_Commission's autumn forecasts re next year:

– Eurozone output gap closed

– Denmark with the same output gap as Spain

– Slovenia looking at the mother of all fiscal consolidations

Feels like there was no sanity check before publishing… pic.twitter.com/2yASFnucoF— Daniel Kral (@DanielKral1) November 15, 2021

Do not underestimate the power of the do-nothing scenario

Next year will likely be the last one when the general escape clause of EU budget rules remains activated, which means that the European Commission is likely to simply rubber stamp the budgets governments have submitted to it without requiring substantial changes.

Soon after, the debate over the reform of the fiscal rules from 2023 will likely heat up. This is seen as a crucial test of the EU’s capacity to learn from past mistakes while making the eurozone more viable. There is a remarkable degree of consensus among economists that the EU’s fiscal rules are not fit for purpose and do not reflect the economic reality of the post-pandemic era, defined by high debt burdens but low debt servicing costs.

Proposals range from ditching the existing rules altogether and moving to a singular focus on debt sustainability to keeping the basic framework but adjusting the numerical targets set out in treaties, focusing on observable metrics (so relying less on structural budget balances and output gaps) or extending adjustment periods. The purpose of all these proposals is to prevent large fiscal tightening in highly indebted economies, with the assumption that the ECB will keep financing conditions favourable.

However, there is absolutely no consensus among member states on the shape of EU budget rules. The frugals, led by the Netherlands, insist on a full return to the status quo ante. The South European governments want to avoid exactly that.

The debate over how quickly EU members should cut down the massive debt accumulated during the Covid-19 pandemic will likely heat up in the coming months https://t.co/7X70GXX3bQ

— Bloomberg Economics (@economics) November 10, 2021

EU ministers to discuss inflation surge, EU budget rule reform https://t.co/OSfnPWXa13 pic.twitter.com/blb5iryhuw

— Reuters Business (@ReutersBiz) November 8, 2021

A key obstacle is, on the one hand, the incentive for high debt economies to free-ride by relying on endless ECB support, and on the other hand, the negative spill-over effects this may bring on others if markets lose confidence and/or the ECB’s support hits its limits. Weak trust among the two groups, compounded by a lack of growth-enhancing reforms in the highly indebted economies during “good times” immediately prior to the pandemic, is a further obstacle.

The obvious landing zone is to make cosmetic changes to the rules, for example by making some green investments exempt from deficit calculations, and continue with weak enforcement of the rules by the EU Commission. In other words, the do-nothing scenario where everyone pretends the emperor has clothes.

In any case, the fiscal adjustment needs should be manageable

Even if the current EU budget rules would be re-imposed without major reforms, the fiscal adjustment needs for the highly indebted economies are not that onerous. This is because, absent a major setback to the recovery, deficits will continue to narrow and public expenditure to fall as extraordinary covid-related measures expire.

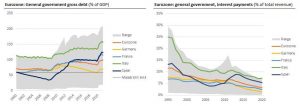

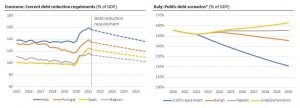

The only EU rule with serious teeth is the requirement to lower public debt by 1/20th of the value in excess of 60% of GDP. For Italy, whose debt to GDP is currently close to 160% of GDP, this means an annual reduction in debt of around 5% of GDP. For Portugal and Spain, it’s roughly 4% of GDP.

In the immediate years prior to the pandemic, only Portugal and Belgium managed to reduce their debt-to-GDP at a sufficient pace. For Italy, it is entirely unrealistic to comply with this rule even under a benign scenario, where the primary balance would return to balance in a couple of years, the effective interest on debt would continue to decline, and nominal growth would average 2.5% from 2023 (versus 2% in 2015-19).

However, there are two reasons why the 1/20th rule should not present too much of a concern.

First, it is backward looking and applies over a 3-year period. Hence, if the rules kick back in 2023, it will be in 2025 at the earliest when this will be assessed. Opinions will be issued along the way, but they will have little bearing.

Second, although treaty-enshrined in the Fiscal Compact (effective since 2013), the 1/20th rule has never been enforced. It’s hard to see why it should suddenly start being applied at the worst possible time for the high debt governments. It may be deployed politically, for example as a threat against a future euroskeptic (Brothers of Italy + The League) government in Italy, but that may easily backfire.

If in the near future Italy has Berlusconi as president and a Brothers of Italy & the League government, things could get interesting. Some in the EU may think twice about reforming the 1/20th debt reduction rule, preferring to keep it in the back pocket to apply pressure. https://t.co/sTOMDibcUW

— Daniel Kral (@DanielKral1) November 17, 2021

In the end, EU budget rules are likely to remain mere paper tigers. Much more consequential will be the capacity of Southern and Eastern European governments to use the sheer volume of their allocated EU funds sensibly, implement the ambitions reforms plan linked to the EU’s Recovery Fund, raise productivity and thereby shift Europe into a higher growth gear. Recent experience is not particularly encouraging on this.

*Benign: Primary balance at 0% from 2025; effective interest at 1.5% from 2027; Nominal growth of 2.5% in 2023-30

Realistic: Primary balance at -0.5% from 2025; effective interest bottoming out at 1.6% in 2026; Nominal growth of 2% in 2023-30

Underperformance: Primary balance at -0.5% from 2025; effective interest bottoming out at 1.7% in 2025; Nominal growth of 1.75% in 2023-30

"The EU's Recovery Fund will not unleash a new economic bonanza across Europe"https://t.co/B91yrZXfyx

New article, by Europe economist @DanielKral1 #NGEU #RecoveryFund #EuropeanUnion— BrusselsReport.EU (@brussels_report) July 15, 2021

Disclaimer: www.BrusselsReport.eu will under no circumstance be held legally responsible or liable for the content of any article appearing on the website, as only the author of an article is legally responsible for that, also in accordance with the terms of use.