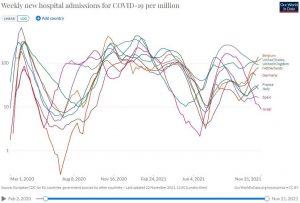

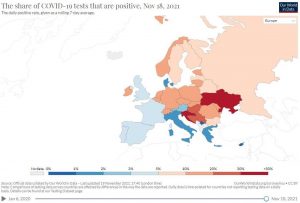

Despite mass vaccination, parts of Europe are being plagued by a new Covid wave, causing countries to implement a whole range of new restrictions. That’s in contrast to the UK, where statistics on both the share of COVID-19 tests that are positive (the “positivity ratio”, which the media should be covering, as opposed to the mere number of positive tests) and the weekly new hospital admissions for COVID-19 per million are looking better or at least more stable than places like Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Austria and Central and Eastern Europe.

New hospital admissions in the UK have been at a higher level for longer however, at least since Summer, which has been attributed to the UK’s earlier vaccination, which is accompanied with earlier waning of the immunity afforded by the vaccines. According to studies, vaccine protection gradually reduces to around half the level as before, over a six month period.

In Israel, which has been a world leader in vaccination, this was visible last Summer, with new hospital admissions peaking at the end of August. Israel managed to overturn this trend by allowing everyone to get a vaccine booster, which adds 81-85% protection against symptomatic infection on top of the protection provided by primary (2-dose) vaccination.

Also the UK is ahead of Continental Europe when it comes to rolling out vaccine boosters. Now, already around 20% of British have received one. In Israel, that’s more than 40%. In the EU, only 5% to 10%.

8) Was Austria 🇦🇹 late on boosters? Yes, like most of the rest of Europe. But Iceland and UK 🇬🇧 are ahead. Israel leading the pack for boosters. And its paying off big time for Israel. https://t.co/ZkUOTEaGWf pic.twitter.com/qqxaXkMGfJ

— Eric Feigl-Ding (@DrEricDing) November 19, 2021

According to a prominent Israeli expert, Gabriel Barbash, an epidemiologist at the Weizmann Institute, “There is no question that the third vaccine, the booster, saved Israel”, however warning that also the protection offered by the third jab “is going to wane and we need to be ready, we need to be cautious about it.”

One doesn’t need to be a communication genius to understand that the prospect of getting jabbed every six months is not exactly something people look forward to, even in the face of evidence it offers protection. Many people will rightly wonder how dangerous Covid really is from them, and many who do not currently take a jab to protect against the flu will decide not to get vaccinated against Covid.

That’s despite the greater health risks from Covid, and despite the pretty clear correlation there is between high vaccination rates and total excess deaths rates. In highly vaccinated Spain, Portugal and UK, there generally are very low excess deaths. In Bulgaria, Russia or South Africa, which all have low vaccination rates, there have been very high excess deaths. In sum, the vaccine works, but its protection wanes after about half a year.

And it’s a similar story if instead of looking at case-fatality-rates, we look at total excess deaths since vaccines began to be rolled out.

Countries with high vaccination rates have generally seen very low excess deaths. Low vaccination? Very high excess deaths. pic.twitter.com/Fa217DkUfF

— John Burn-Murdoch (@jburnmurdoch) November 1, 2021

What should governments do and what have they done?

The obvious response to understandable hesitancy to get booster vaccines is to let people themselves make the decision whether they get vaccinated or not and whether they get a third or perhaps – next year – a fourth jab and to make sure there vaccine booster are actually available. Governments in the EU have been failing on both accounts.

First of all, they have been slow with allowing those that want a booster vaccine to get one, this unlike the UK, Israel, Iceland and the United Arab Emirates. The U.S. has been equally slow.

Secondly, governments have not exactly been leaving the decisions to citizens. Austria has gone as far to introduce mandatory vaccination, preceded by a short dystopian “lockdown for the unvaccinated”. That was before depriving the unvaccinated from entering venues even if they were tested, something which is complete scientific nonsense, given that those vaccinated are still able to spread Covid – less so, however- while the unvaccinated that have been tested negative are obviously not contageous. This so-called “2G” policy has been copied in parts of Germany, which may now go further, as well as the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Latvia has probably gone the furthest, depriving unvaccinated members of Parliament from the right to vote, something completely undemocratic.

EU weighs changes to Covid certificates, travel rules during surge https://t.co/2scxosEs1b via @JohnFollain @DeutschJill pic.twitter.com/yx1cptMQ29

— Zoe Schneeweiss (@ZSchneeweiss) November 22, 2021

The sinister expansion of the EU’s Covid Passport to domestic restrictions

It was only a matter of time before the EU’s Covid Passport, originally meant for travel, was going to used domestically, something authors at Brussels Report have been warned against.

Obviously, Covid remains a great challenge, but measures like banning unvaccinated people that have been tested from entering certain venues objectively do not contribute to the laudable policy aim to prevent Covid from spreading.

“COVID-19: stigmatising the unvaccinated is not justified”

“There is increasing evidence that vaccinated individuals continue to have a relevant role in transmission”

By Gunter Kampf, 20th November 2021 @TheLancet Correspondence https://t.co/BVVVqoBsfx

— Maajid أبو عمّار (@MaajidNawaz) November 21, 2021

Even if these kinds of severe restrictions would convince some of the unvaccinated to get vaccinated after all, it will certainly also embolden some of them in their opposition to the vaccine.

The precedent of governments bullying a large part of the population into a certain medical procedure should raise serious question marks, even if in Israel, the success of the booster campaign was linked to the fact that people were no longer considered “vaccinated” to get Israel’s domestic version of the Covid passport.

Mandatory vaccination

Then is mandatory vaccination a better alternative? There are cases for mandatory vaccination to be made – smallpox or polio come to mind – but can this be justified for Covid? Over the weekend, Belgian PM Alexander De Croo, who’s an opponent of mandatory vaccination, expressed doubts whether such a legal obligation will even convince people to do so in practice.

Alternatives

The more sensible approach, in my view, is to make sure that vaccine booster campaigns get a boost themselves.

Apart from this, the argument that the unvaccinated disproportionally burden health care is absolutely correct, but this can be mended through simply applying a traditional practice of insurers: people are free to take extra risks, but this comes with a higher fee to be insured for medical care.

Naturally, European health care systems are mixed public-private systems, which makes it a lot more tricky to implement this, but as I have argued before, it could be an idea to charge an extra “Covid health insurance fee” for the non-vaccinated, if it can be effectively proven that they form an extra burden on healthcare – with people being able to challenge the assertion that the conditions are met in Court. As far as I am concerned, it could also be applied to all kinds of other behaviour. The more insurance companies know about behaviour, the more they can reduce the price for everyone.

In practice, this would mean that a young person declining a vaccine would only need to pay a very modest extra fee, given the low chance to be hospitalised, but if someone belonging to a risk group refuses the vaccine, the fee would be much higher. Obviously, that money should only be used for Covid-related healthcare for the unvaccinated, which should make sure people do not see it simply as some kind of a fine for not being vaccinated but as a justified extra insurance premium.

In the near future, we can expect medication to treat Covid. Covid passes, institutionalised discrimination and arbitrary government policies may in the meanwhile however do a lot of harm to the social fabric.