The Covid crisis and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have triggered a major debate about Europe’s dependency on the rest of world for anything considered of strategic importance. Naturally, this is not always easy to define, and protectionists of all stripes will always attempt to abuse this justified concern for their sinister cause, but at the end of the day, it is a legitime debate to be had.

This is especially evident witnessing how energy-dependent Germany had become of Russia, even if it should be realized that this dependence was not the outcome of some kind of market-driven process, but the direct result of policies to phase out nuclear power and also domestically produced fossil fuels. Surely any European opponent of fossil fuels should go about the endeavour by first cutting down on imports of non-European fossil fuels before shutting down Europe’s domestic fossil fuels industry, but clearly, this isn’t what happening, leaving European policy makers with a massive challenge.

China

Notably, the European Union is incredibly dependent on China for rare earth elements – for 98 percent, according to the European Commission. That is a lot more than the dependence for natural gas on Russia before the war. Then, it sourced 40 percent of the natural gas it consumed from Putin and partners. “Rare earths” are of great economic importance and particularly key to achieve the EU’s desired “ecological transition” away from fossil fuels. These elements are vital for wind turbines and EV motors.

In order to address this, the European Commission is coming up with a so-called “EU Critical Raw Materials (CRM) Act”, which it intends to officially propose in 2023. At the moment, China enjoys a quasi-monopoly position, with 19 out of the 30 most critical raw materials imported primarily from there. Apart from rare earths, this also includes materials like lithium and magnesium.

EU to introduce targets for raw materials self-sufficiency https://t.co/th2KN3bLQ7

— EURACTIV (@EURACTIV) December 9, 2022

Practically, the Commission intends the new legislation to help diversify and increase sourcing of these materials from non-member states and to remove distortions to international trade. It also wants to increase domestic sourcing, both when it comes to mining and refining materials.

Getting the EU Critical Raw Materials Act right

A submission to the European Commission by Brussels-based think tank European Foundation for Democracy makes some valuable suggestions to make sure the legislation gets its right. It stresses that the EU should aim to “have meaningful impact on efforts to avoid economic relationships with countries that engage in the violation of human rights”. This includes China, whose state-owned companies profit from Uyghur slave labour as Beijing engages in anti-competitive government intervention that undercuts competition.”

The problem in China with forced labour in supply chains has been widely documented and highlighted by the West. Separate EU legislation is being rolled out to counter this, but The EU CRM Act could be useful as well here, so including provisions on forced labour in it makes sense, also how to avoid unfair competition with private companies from democratic countries that adhere to all human right standards.

"To counter forced labour in supply chains, a targeted approach is preferable"

New article by @pietercleppe:https://t.co/FhMAp6ML3I #duediligence #EU— BrusselsReport.EU (@brussels_report) July 14, 2022

As an example, the European Foundation for Democracy cites how “the People’s Republic of China has developed advanced infrastructure networks throughout mineral-rich regions, such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, which produces 70% of the world’s cobalt. This metal’s primary use is in the manufacturing of rechargeable battery electrodes. Cobalt is also used in superalloys, materials that help make parts for gas turbine engines, and in a range of other applications in the commercial, industrial, and military sectors.”

Particularly interesting is how the Chinese government already uses its leverage. In 2021, Chinese authorities ordered state firms to curb their overseas commodities exposure and pressured companies to cap thermal coal prices, all in a bid to undercut foreign competition. They also publicly declared to sell metals from state reserves as a way of manipulating world markets.

Perhaps the name of the political party which is in charge should have given it away that the “Chinese Communist Party” (CCP) is not exactly averse of totalitarian central planning.

To become increasingly dependent on China means to become increasingly vulnerable to the effects of these central planning distortion.

Cooperation between like-minded democracies

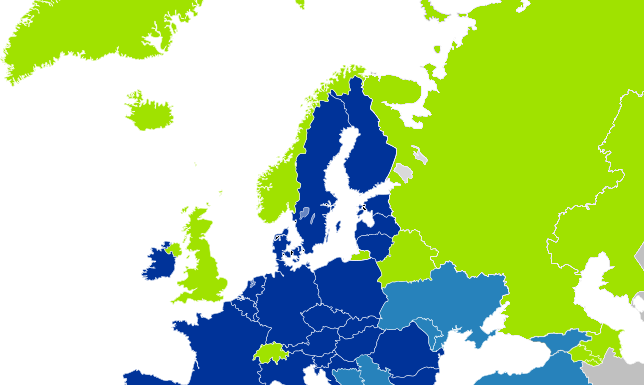

Cooperation between like-minded democracies is one evident step to avoid the pitfalls of excessive economic dependence on authoritarian states. For this, in June, the United States announced the establishment of the Minerals Security Partnership (MSP), together with Australia, Canada, Finland, France, Germany, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Sweden, the United Kingdom, the United States, and the European Commission. The goal is to «ensure that critical minerals are produced, processed, and recycled in a manner that supports the ability of countries to realize the full economic development benefit of their geological endowments.”

Also trade ties with countries like Chile, the world’s second-largest producer of lithium (after China), could be strengthened, for example by finally completing the EU’s trade agreement with Mercosur. The incoming Swedish EU Presidency intends to prioritise this.

This illustrates how caring about geostrategic dependence can and should go hand in hand with greater free trade, not protectionism.

EU upgrades deal with Chile in bid to beat China to vast lithium reserves

https://t.co/tS1jOeck1F— Finbarr Bermingham (@fbermingham) December 9, 2022

Furthermore, it makes little sense to do business with crony state companies from authoritarian countries while there are publicly traded multinational companies that adhere to certain standards. Simply requiring minimal standards to be met, like absence of state control or of forced labour in supply chains, can already contribute to reducing dependence on the likes of China.

Both when it comes to cobalt exploration in the Democratic Republic of Congo or lithium from Chile, private companies that adhere to acceptable standards are already active on the market. Even if one thinks that it would be hard to source certain materials from non-dodgy suppliers, it is a good idea to make sure that the real cost of for example electric vehicle (EV) batteries is ultimately reflected in the price. Perhaps shutting out crony state companies from the supply chain will no longer make electric vehicles economically feasible, but it clearly is more important not to be dependent on authoritarian suppliers and avoid human rights violations in supply chains.

To bring a kind of “democratic level playing field” to the international market, rooting out cronyism and ensuring the compliance with human rights, really isn’t different from the level playing field the EU is tasked to ensure within its own internal market. The idea here is of course not to impose the EU’s specific regulatory choices to the rest of the world but to simply counter blatant cronyism by requiring minimal standards from companies importing into the EU.

In sum: in order to avoid undesirable geostrategic dependence, there is an alternative to protectionism. Cooperation with different regions and countries and publicly traded multinational corporations can help diversify the supply chains for scarce materials and reduce Chinese dominance in CRM production and processing.