By Ogechukwu Egwuatu, a columnist with Young Voices Europe and a France-based student, writer and campaigner. She is also a local coordinator with Students For Liberty.

The European Commission recently presented a proposal to increase the bloc’s revenue sources as part of mid-term reviews of its seven-year budget. In recent years, the EU’s expenses have risen rapidly as crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine and inflation have put pressure on the bloc’s finances. The proposal as well as talks leading up to it have centred around creating independent revenue sources for the EU rather than relying on the contributions of the member states. While most of the measures suggested in the proposal are simply extensions of already existing measures, the conversations around EU funding and its future require discussion. This is an opportunity for the EU to reflect on its strategy for solving the problems it’s faced with.

One thing that both the proponents and opponents of this proposal agree on is that this cannot solve the EU’s funding problem. The provisions made in the recent proposals which will raise the EU’s own funds to about €16 billion a year as of 2024 are not likely to bring in enough funds to support the EU’s ambitions which keep increasing. For example, despite assurances that the required funds would be taken out of an already existing budget, there have been doubts about the availability of funds for the proposed Strategic Technologies for Europe Platform (STEP) and this situation is not a unique occurrence.

Some have called for the EU to tax the wealthiest and financial taxes. However, it is important to ask how realistic this is and more importantly, if it is the right approach.

A major problem with the EU’s approach is it seeks to solve its problems with a complex entanglement of taxes and subsidies, endangering its founding principles of free and fair trade. The bloc employs strategies that favour big businesses when it comes to issues like subsidies and restrictive regulations as they have better resources to lobby for these to favour them at the expense of smaller companies who do not have these resources. At the same time, it aims to fund these subsidies and projects by targeting big businesses with increased taxes. The result seems to be a delicate balance of push and pull which leaves only a few winners in the game. This also leads to conflicts with its future ambitions. For example, despite ambitious green energy and climate protection plans, the EU is currently caught in a clash over discontinuing coal subsidies and has to work on phasing out quite a number of environmentally harmful subsidies.

Surely if there is one budget where savings are easy to find, it is the #EUbudget… EU taxes as a means to compensate for the EU overlooking the risk of higher interest rates: not a vote winner, I'm afraid. https://t.co/e3mJvGCd7R https://t.co/b9YhFA7KH6 #MFF #RRF #NGEU #cuts

— Pieter Cleppe (@pietercleppe) June 28, 2023

EU taxes are the wrong policy recipe

With its declining competitiveness, deindustrialisation problems, inflation and the US’ and China’s subsidy race, taxes seem like a shaky foundation to build the Commission’s “strategic autonomy” on. It has to consider the reticence of member countries to give up decision making powers or privileges over issues that concern their sovereignty and national interests while taking care not to make companies feel overburdened by a complex tax system and numerous levels of taxation especially as the bloc is trying to get companies to pay taxes in the region.

The EU needs to create realistic and sustainable solutions to its problems. The EU cannot tax its way to wealth.

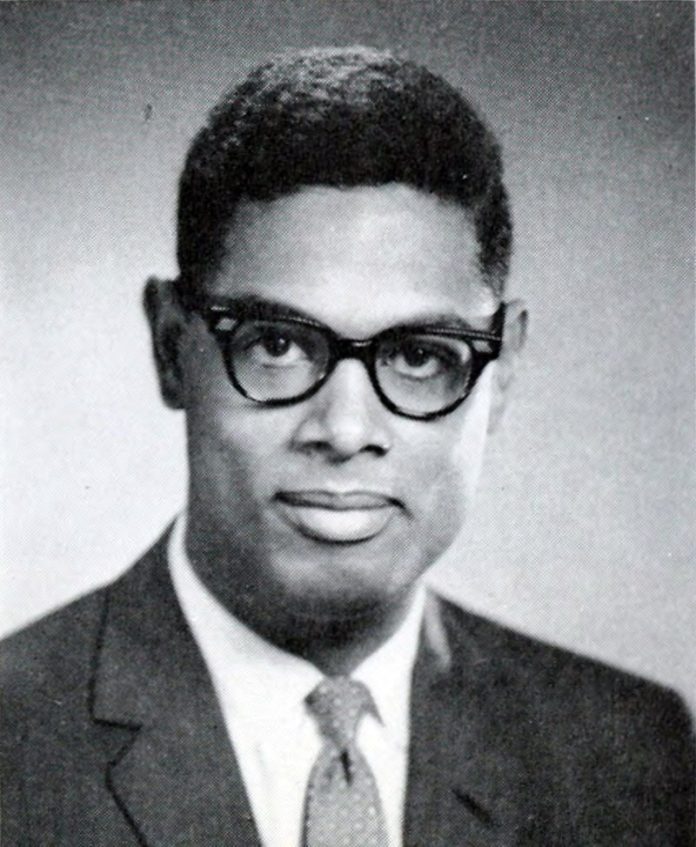

According to Thomas Sowell (picture), “Wealth is the only thing that can cure poverty”. It is important to look back at the foundation of the EU. which is also what has brought it much prosperity so far: free and fair trade. Being realistic does not mean having no ambition or not aiming to solve problems that seem to have no solution. It means thinking of the most practical ways to solve problems while taking into account the consequences of our choices and that Europeans and even people living in other parts of the world would have to live with these decisions. It is remembering that the quality of life of these people and the durability of the solutions proffered matter more than good press drastic measures make.

One of the biggest, and one of the oldest, taxes is inflation. Governments have stolen their people’s resources this way, not just for centuries, but for thousands of years.

— Thomas Sowell Quotes (@ThomasSowell) September 13, 2022

d