This week, the Eurozone’s annual inflation rate reached 3%, which marks a 10-year high and is also way above the ECB’s 2% inflation target.

Eurozone inflation beat expectations again: YoY .3 percentage points higher than estimate; MoM .2 percentage points higher. #Eurozone #inflation trending higher, following US inflation with a lag. https://t.co/smyo5egNou

— Fabian Wintersberger (@f_wintersberger) August 31, 2021

Euro area #inflation up to 3.0% in August: energy +15.4%, other goods +2.7%, food +2.0%, services +1.1% – flash estimate https://t.co/niimGPKpb8 pic.twitter.com/RsmrfKLPYi

— EU_Eurostat (@EU_Eurostat) August 31, 2021

Source: Eurostat

In particular energy prices seem to be a driver, as they recorded a 15.4% annual increase in August, which is much higher than the price increases of industrial goods excluding energy (2.7%), food, alcohol and tobacco (2%) and services (1.1%).

Eurozone inflation is high while the rise in essential goods and services exceeds the official print. pic.twitter.com/fGi4O7AKMB

— Daniel Lacalle (@dlacalle_IA) August 30, 2021

Some economists have argued this is due to the reopening of economies and supply issues. All of those things should be temporary, even if supply issues persist for 18 months now. It should not come as a surprise that also many within the European Central Bank think along those lines.

EU climate policies

Obviously, Covid and its extreme effects are part of the explanation, but given how badly energy prices are affected, there should be a link with the increased price of CO2 emission permits. The EU’s climate policies are truly biting.

Interestingly, Spain is experiencing particularly higher inflation than Italy and France. In August, the Spanish leftwing government already urged the EU to use existing legislation to restrain or push down soaring carbon trading prices, as Spain’s electricity prices have reached a record high.

According to the FT, “Spain, which depends on foreign sources for almost three-quarters of its energy mix, is particularly exposed because of its reliance on liquefied natural gas, for which it has to compete with increasing demand in Asia.” According to Spanish economist Daniel Rodríguez Asensio, this reliance is due to Spain’s dependence on renewable energy sources, which account for 40% of energy production but are in turn dependent on back-up energy sources like natural gas – when there isn’t enough sun or wind. Nuclear energy only accounts for 25% of energy production. Apparently, CO2 prices would only account for 20% of Spanish energy invoices, according to the Spanish Central Bank. And of course, about half of Spanish energy bills consists of taxes. In a nutshell: the high energy prices of Spain – but also in other Eurozone countries – have a lot to do with domestic mismanagement.

The ECB as the elephant in the room

While energy policy mismanagement and Covid may definitely be to blame for increased prices, the elephant in the room should of course not be overlooked: the European Central Bank and its extremely expansionist monetary policies. This week, the ECB’s balance sheet reached a new all time high, as a result of the ECB buying up assets through its various “quantitative easing” programmes, all financed with newly created money. The ECB’s total assets are now equal to almost 80% of Eurozone’s GDP, which is a lot more than in the U.S., where the Fed’s total assets only equate 37% of U.S. GDP and in the UK, where the Bank of England’s total assets amount to 39% of UK GDP. We’re still not at Japan’s level, where that figure is 133%.

#ECB balance sheet jumps by a whopping €139bn to hit fresh ATH at €8,191.3bn on QE and as Receivables from IMF gained €122.4bn. ECB's total assets now equal to almost 80% of Eurozone's GDP vs Fed's 37%, BoE's 39%, and BoJ's 133%. pic.twitter.com/8BuzpXNrM6

— Holger Zschaepitz (@Schuldensuehner) August 31, 2021

Again, there there are other factors than money “printing” – technically, monetary expansion by both ECB and private banks – but the graph below clearly shows a degree of correlation between inflation and monetary expansion. When the ECB’s balance sheet is up or down, the consumer price index (CPI) tends to go up or down as well:

It looks like money printing is fueling inflation after all. The only question is whether inflation is a transitory phenomenon or whether inflation will now continue to follow the #ECB's balance sheet upward? pic.twitter.com/PzDHRBxWar

— Holger Zschaepitz (@Schuldensuehner) August 31, 2021

The ECB under political fire

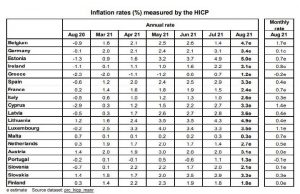

In August, only in Belgium, Luxembourg and the Baltics, inflation was higher than in Germany. Also other metrics point a bleak picture. It should therefore not surprise to see German media and politicians targeting the ECB.

#Germany is #inflation champion in the Eurozone. Even if you compare inflation trend since 1999, Germany has suffered a greater loss of purchasing power than France and will soon catch up w/Italy, which has a very different inflation culture. https://t.co/fnJRXy6zCM via @welt pic.twitter.com/YyoWkr4CKb

— Holger Zschaepitz (@Schuldensuehner) September 1, 2021

The front page of @Bild today. Have a nice day. pic.twitter.com/7Q2ozhJXpn

— Pawel_Tokarski (@Pawel_Tokarski) August 31, 2021

Good morning from Germany, where #inflation fears are rife. Meanwhile, there is already a 1000 euro bill with the likeness of #ECB President Christine Lagarde, published by the popular newsletter Steingart Morning Briefing. pic.twitter.com/h22ePM6IVE

— Holger Zschaepitz (@Schuldensuehner) September 2, 2021

Christian democratic politician Friedrich Merz, who may become the new finance minister if his party manages to stay in power, has even warned that “the ECB is pushing against the limits of its mandate”, also criticizing the ECB Governing Council’s decision to raise its inflation goal to 2% (another “Dovish” policy change”, which now involves the ECB aiming for a 2% headline inflation rate over the medium term). It should not surprise to see these kind of political attacks against the ECB, given the German elections later this month.

Merz, until last year the Chairman of BlackRock Germany, also mentioned how the ECB made “renting” and “buying real estate” more expensive. Politicians like him seem to wake up to the fact that the ECB carries an important responsibility for the skyrocketing housing prices, also in other Eurozone countries, like the Netherlands.

Good Morning from #Germany, where the housing boom accelerates as Germans are buying real estate fearing rising inflation & rents. Europace House Price Index has risen in tandem w/ECB balance sheet to ever new ATHs. Jumped 1.9% in June. German House Price Index is now up 8.7%YTD. pic.twitter.com/HuP93lZDCc

— Holger Zschaepitz (@Schuldensuehner) July 25, 2021

German house prices: +12.4% y/y in Q2 '21.

The ECB is causing price inflation big time. pic.twitter.com/YB4lsxXakK

— Thorsten Polleit (@ThorstenPolleit) July 29, 2021

Internal ECB opposition

At least, as reported on Brussels Report, within the European Central Bank, the hawks are finally somewhat resisting. Following an internal row in July, German, Dutch and Austrian Central Bank bosses have once again issued hawkish comments, following the latest inflation data, with calls to end extraordinary ECB measures. This was countered by dovish statements coming from Greece’s Central Bank.

* ECB HAWKS ARE FLYING *

ECB Holzmann Says ECB Should Discuss Cutting Crisis Aid Next Week … BBGhttps://t.co/RJ3nvpIKAN

ECB Knot : Euro-Area Inflation May Justify End to ECB Crisis Mode … BBGhttps://t.co/fRSMde4uQb pic.twitter.com/k8Ip8AArUS

— Trading Floor Audio (@TradeFloorAudio) August 31, 2021

Bundesbank President Jens Weidmann says ECB officials shouldn’t disregard the risk that inflation could accelerate faster than currently anticipated https://t.co/lixEQZOSrV

— Bloomberg Markets (@markets) September 1, 2021

According to banking analysts, the ECB would now be planning to announce the reduction of its Covid-related stimulus, aka “tapering”, in December. Then, one of its QE programmes, the so-called “Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program” (PEPP), worth 1.85 trillion euros, is supposed to end in March 2022 anyway. Unlike under “regular” QE, the ECB used its pandemic programme to buy up Greek government debt, which may help explain why Greece can borrow more cheaply than the United States. At least, that’s what the official market prices reveal. In practice, the only buyer of government debt in Southern Europe is the ECB:

When people say Spain (lhs) & Italy (rhs) have lots of fiscal space because yields are low, that's not quite true. The only buyer of gov't debt in both places is the ECB (blue). Private investors are staying away, so aren't convinced there's lots of space. With @JonathanPingle pic.twitter.com/fxTa27gUDW

— Robin Brooks (@RobinBrooksIIF) August 15, 2021

Awaiting economic growth

The key question now is whether inflation in the Eurozone will actually be “transitory”, as the ECB claims. Looking at the so-called “producer price index” (PPI), things are not looking rosy. Inflation seems to follow PPI, which is now up to 12.1%, the highest PPI ever in the Eurozone, breaking the 2007 record:

#Eurozone #PPI at 12.1% (exp. 11.1%) – highest PPI on record. https://t.co/jDV2y1C5BY

— Fabian Wintersberger (@f_wintersberger) September 2, 2021

Here's the chart:#Eurozone #PPI https://t.co/6c5l3lPEtv pic.twitter.com/nCJNi930zu

— Fabian Wintersberger (@f_wintersberger) September 2, 2021

As Austrian economist Fabian Wintersberger explains: “An increase in PPI will put more pressure on businesses to raise prices at some point”.

However, make no mistake about it: even if official inflation would fall, that does not mean that the extraordinary policies of the ECB did not come with a cost. It is entirely conceivable for prices to fall as a result of the dire economic fallout of Covid, despite upward pressure on prices as a result of the ECB’s monetary expansion. In such a scenario, prices would simply have fallen even more if it weren’t for the ECB’s manipulation.

Whether prices will increase or fall, the most important thing is therefore for sustainable economic growth to emerge. Here, GDP growth of big economies, certainly the Eurozone economy, is still below the pre-Covid trend.

Advanced economies GDP is still below its' pre-covid trend. Although it seems that delta won't be that much of a deal for the world economy, I suspect that all growth projections are still too optimistic because stimulus fails to create sustainable growth.https://t.co/g9Df4hFrSm pic.twitter.com/ATJku4tgVd

— Fabian Wintersberger (@f_wintersberger) September 1, 2021

Politicians only have a limited ability to influence economic growth. For one, the EU’s 800bn euro “recovery fund”, is unlikely to do much good. However, if increased prices are not accompanied with increased economic growth, the ECB is likely to become a more frequent target for politicians eager to find someone to blame.