By René Cuperus, a Dutch international affairs scholar. Amongst others, he is a Research Fellow at the Germany Institute of the University of Amsterdam.

“Who’s afraid of Germany? For the Dutch, this seems like a question out of history books. After all, there hasn’t been any fear of Germany for decades, has it? When it comes to football, perhaps, but politically? Surely Germany has become a truly exemplary democracy after World War II?

Germany is a member of the European Union and NATO, and therefore, it has become an indispensable pillar of the Transatlantic Alliance, also known as “the West”. Longtime Chancellor Angela Merkel has brought peace, purity and order to both Germany and Europe, the thinking goes.

Perhaps even a little too much peace and order. After all, is anyone still afraid of Germany? One might have hoped that Putin’s Russia would fear Germany a bit more. That might have deterred Putin from annexing Crimea and the MH 17 would have never been brought down.

Or suppose that China had been a little more afraid of Germany. Then it would have acted less abrasively in Eastern Europe and the Balkans, and Germany’s important China think tank, MERICS, would never have been sanctioned.

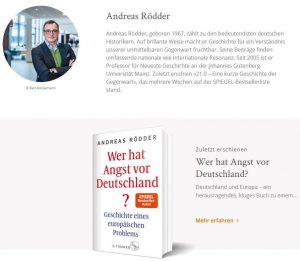

However, it is not this fear of Germany that we are talking about. Here, I’m referring to the title of a 2018 book by well-known German historian Andreas Rödder: “Who’s afraid of Germany? A history of a European problem”.

In this book, Rödder recalls how most of European history has been dominated by “the German question” or “the German problem”. What does that mean? It means that Germany, as the “Central power of Europe” is too small to control Europe, but too big and too strong to be one of its many small countries. It is condemned to what has been called a “semi-hegemonic position” in Europe.

Prussian Power

For a long time in European history, the German question has been solved, especially by France and England, by means of making sure that Central Europe was weak and divided. Germany at the time was divided into kingdoms, and became Napoleon’s plaything. Things only went wrong with German unification under Otto von Bismarck (picture), when he managed to establish the Prussian-German Empire in 1871.

Suddenly, a new superpower had emerged in the center of Europe, which would lead to a complete destabilization of the European balance of power. This resulted in the First and Second World Wars, the disasters of the twentieth century.

First: Taming Germany

The central issue remained: how to tame German power and reconcile it with Europe as a whole. The Peace of Versailles in 1919 had provided for every means to break German power, including demands for reparations and submitting parts of Germany under French occupation. This “humiliating” peace caused revanchism and revisionism, and it culminated in the catastrophe of Nazi Germany.

After World War II, a new attempt was undertaken to curb German power. The country was divided into occupation zones, which would end in the German partition, between a Federal Republic and the GDR. Because of the Cold War, the Federal Republic was fully integrated into the Western alliance composed of NATO and the European Community (Westbindung).

Then: Reconciling Germany

Prussian militarism was defused by submitting the military-strategic Ruhr region to the European Coal and Steel Community, thereby bringing reconciliation between hereditary enemies France and Germany. These conditions enabled the Federal Republic to develop into a functioning liberal democracy.

Germany was no longer a Prussian-romantic “Kulturnation” opposed to Western civilization. It had now finally arrived in the West. The postwar Federal Republic was characterized by foreign policy and military ‘restraint’. It preferably saw itself as a “Zivilmacht” (civil power) and “Friedensmacht” (peace power), pursuing ‘soft power’ over ‘hard power’.

Only with the second German reunification – not Bismarck’s, but Helmut Kohl’s – would the question ‘Who fears Germany?’ pop up again. Wouldn’t a reunified Germany once again become disproportionately large and powerful on the European continent? Would the reconciliation with France not be strained by that new difference in power?

Chancellor Helmut Kohl’s diplomacy was impressive, as he used the superpowers, America and the Soviet Union, to force German unification through. By doing so, he overrode the reservations of his European partners at the time.

Rödder’s book takes a closer look at the positions of French President Mitterrand, British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and Dutch Prime Minister Ruud Lubbers. All three of them had reservations with regards to German unification. For understandable historical reasons.

Weakening Germany

Wouldn’t German unification again destabilize the European balance of power? In France in particular, there was great concern about whether Germany and France would still be able to be “at eye level ” with each other. The answer to all these concerns and reservations ultimately became the euro, the Monetary Union.

French President Mitterrand called the German Mark the “German atomic bomb”. Just as the Coal and Steel Community was meant to weaken German power by Europeanizing it, the European Monetary Union was meant to defuse German economic and monetary dominance. That was the price for German unification and the solution to prevent and defuse German dominance over Europe.

Germany ‘restrained’

Not every European realizes that European unification is the – geopolitical – price for German unification. The Chancellor of German unification, Helmut Kohl, has been very clear about this himself, as he stated:

‘The question of the construction of the European house with the irreversible restraining of the country that is the strongest by far, Germany, is the question of war and peace in the 21st century’

In other words, European integration must and cannot be other than irreversible. That is the only way to structurally “restrain” German power, so to contain it. That’s nothing less than a matter of war and peace.

Seen in this way, German unification has burdened the fortunes of European cooperation with an enormous mortgage. One could say that the generation of Kohl, Mitterrand and Lubbers/Kok engaged in a major gamble with history. Perhaps an irresponsible gamble. To declare for future generations, to declare for the further course of history, something “irreversible”, is little different than to engage in historical hubris.

Now: more Europe?

Who is able to say exactly how European unification will develop? Look at Brexit. Look at the tensions between East and West, North and South or how the “European Community of Values” and the Monetary Union may be divisive rather than unifying.

This whole complex of problems is facing additional pressure as a result of the new geopolitical context the world has entered: the advance of Asia and the decline of the West. All around Brussels and beyond, we can now hear calls for “European sovereignty,” for “European strategic autonomy”.

America is described as having become untrustworthy since Trump. Authoritarian powers like China, Russia and Turkey are supposed to face more opposition, amid calls for more geopolitical unity, power and capacity to act for Europe.

“More Europe” means more German power

What’s not really being said about this is that all of this requires a very different kind of Germany: a Germany which drops its postwar foreign policy and military restraint, and which instead takes up more leadership in Europe.

With this, we encounter, as Rödder calls it, a new German dilemma. On the one hand, Europe requires more German leadership, but when it exercise it – as for example during the Euro crisis or during the refugee crisis – it is quickly accused of dominating everyone else or of “going it alone”. Then people in Greece or Poland once again fear Germany.

And the Netherlands? Should it once again fear Germany? If so, not because of ancient historical ghosts, but because of fear for marginalization. Because what is somewhat frightening, is that the Netherlands comes out very poorly in this German work by the famous historian Rödder. It appears as a small country which is hardly worth mentioning.

In the Netherlands, we think we can keep up reasonably well with our Great Neighbour. Some even think that there would be something like a “special relationship” between Germany and the Netherlands within the EU. However, for Germans engaged in analyses of geopolitics and “Realpolitik”, the Netherlands is apparently easy to ignore.

In our foreign policy circles, for example, the Netherlands is thought to be an important soul mate of Germany in the struggle between North and South in the Monetary Union (solidarity versus solidity), but in Rödder’s book, it is not the Netherlands, but Finland, which is mentioned as Germany’s Monetary Union ally. In the Netherlands, we boast that it was us, together with Chancellor Merkel, that concluded the Turkey deal during the refugee crisis, but also here, the Netherlands is not mentioned.

It is even worse. Everyone that is fashionably joining the calls for Europe to become a stronger geopolitical unit, to speak more with one voice in the raw outside world, does not realize that in doing so, they are forcing a rock-hard divide between large and small countries within the EU, and therefore breaking one of the taboos within the EU: the factual difference in power between large and small countries.

“More Europe” means less power for the small ones

It’s worth minding the advice of historian Rödder, who’s affiliated with the CDU. In order to achieve more powerful European leadership, he proposes the creation of a geopolitical partnership between Germany, France and the United Kingdom. He calls this the “Elysée à trois”, after the postwar Elysée Treaty between France and Germany. This directorate of three great nations would have to direct Europe not only militarily and when it comes to foreign policy, but also scientifically and technologically.

The German historian acknowledges the danger that smaller European countries may feel excluded and marginalized. Therefore, he suggests the a “consultation à six” should also be possible: with Spain, Italy and Poland. No Netherlands, which is ranked somewhere amongst Belgium, Austria and Denmark.

In sum, there is some reason to fear Germany developing itself geopolitically. That may be good for Europe, but bad for the self-esteem of the Netherlands.

This article was originally published in Dutch by Wynia’s Week.

Disclaimer: www.BrusselsReport.eu will under no circumstance be held legally responsible or liable for the content of any article appearing on the website, as only the author of an article is legally responsible for that, also in accordance with the terms of use.