This week, the so-called “COP26” United Nations climate talks have started in Glasgow, where more than 120 leaders are about to reportedly negotiate “a plan to rapidly decarbonize the planet”. Conspicuously missing are the leaders of China and Russia, amid China shying away from overly ambitious “climate” pledges. The country has been expanding coal mines to produce 220 million metric tons per year of extra coal, something which isn’t exactly reducing CO2 emissions. This is a nearly 6 percent increase as compared to 2020. China is already digging up and burning more coal than the rest of the world combined.

Speaking at the UN event, European Commission President Ursula Von der Leyen had a go at them, saying she “would have liked to see China and Russia being here”, urging China to “step up and show what they are going to do”.

Rumour has it @vonderleyen is going to send China and Russia … a letterhttps://t.co/bsYHj6lifI #COP26 #COP26Glasgow #nuclear #coal #gas #renewableenergy pic.twitter.com/tLDZbLgQLN

— Pieter Cleppe (@pietercleppe) November 1, 2021

In fact, it’s not just China which is addicted to coal. In the whole of Asia, which is home to 60% of the world’s population and counts for half of global manufacturing, the use of coal has been growing instead of shrinking, due to energy demand. Also in the U.S., coal is the second most used fuel in US electricity as it also remains key for some European countries.

Then Asia really is the coal hotspot. Of the 195 coal plants being built around the world at the moment, more than 90% are in Asia. “We cannot depend on just solar and wind,” a senior official of the electrical power generation and distribution public sector undertaking of India’s second-most industrialized state, Tamil Nadu, told Reuters. Notably, the state is one of India’s top renewable energy producers. However, it is also building the most coal-fired plants in the country. The official added: “You can have the cake of coal and an icing of solar”.

Also Japan is turning to coal by building seven large new coal-fired power stations. It is planning to restart 30 new nuclear reactors, but this takes time.

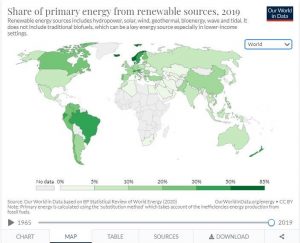

In Europe, both Belgium and Germany are abandoning nuclear energy. To prevent blackouts, both countries are intending to rely more heavily on gas as a “transition fuel”– apparently oblivious to how this increases Russia’s political leverage. This policy is supported by the greens in both countries, who are adamantly opposed to nuclear energy. It really is in line with what international conferences like COP26 have always pushed for: no gas, no oil, no coal, no nuclear, but renewables. However, despite all the policy support renewables have enjoyed, they are still only a marginal source of energy. The “transition” may therefore take way longer than promised.

In 2019, only 11% of global primary energy came from renewable technologies. That includes hydropower, solar, wind, geothermal, bioenergy, wave and tidal. It is important to distinguish energy from electricity generation, to which renewables contribute a higher percentage. The electricity sector makes up only 17% of the total energy the world uses.

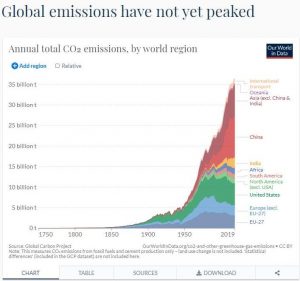

During the last few decades, global CO2 emissions have continued to go up, despite COP26 – style gatherings and the almost cult-like attention for activists like Greta Thunberg (see picture). While a modest reduction can be witnessed in the West, emerging economies have been pumping CO2 into the atmosphere in ever greater quantities.

China isn't listening, though. pic.twitter.com/qjsFHbYM8A

— Stop Being Silly 🇬🇧 (@British_Ideas) November 1, 2021

In sum, attempts to reduce CO2 have resulted in failure. The excessive focus on solar and wind – instigated by global policy communities – has not been of any help here. Declaring nuclear energy – which the EU now finally seems to be contemplating – as something that is useful to reduce CO2 emissions is really nothing more than a statement of fact. Wind and solar energy need some kind of back-up when the wind does not blow and the sun does not shine, given the limited ability of batteries. There are three options for that really: coal, gas and nuclear. Of those three, only nuclear energy actually avoids CO2 emission. In sum, it’s hard to be concerned about CO2 emissions without exploring nuclear energy as a possible fix.

Still, despite the hysteria, witnessed by the UN secretary-general declaring nations are “digging [their] own graves” by using fossil fuels and that “failure is a death sentence”, COP26 organisers are deliberately pushing the nuclear energy option aside. Reportedly, they told nuclear industry advocates to set up shop in the meeting’s quieter “Blue Zone” instead of the public “Green Zone”, where companies enjoy higher visibility. Rafael Mariano Grossi, director general of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) recalled: “At COP25 I was warned not to even attend.” This all despite calls by the likes of the American Nuclear Society, which represents 10,000 nuclear engineers, scientists, and technologists, to not favour nuclear energy but simply treat it “on a level playing field with other clean energy technologies.”

The oil industry has even befallen an even worse fate. COP26 organisers imposed an outright ban on oil firms, like Equinor, Shell and BP, taking an active role in the UN conference, which they had offered to help sponsor. It can serve as yet more evidence of the sectarian mood at these kind of conferences when corporates that are at the heart of our energy system are pushed out of the conversation about decarbonising and reducing reliance on carbon-based energy.

COP9

Things are not much better at another, similar international conference, called “COP9” – organized by the World Health Organization (WHO), this time in The Hague. This so-called “Ninth Session of the Conference of the Parties” (COP9) to the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (WHO FCTC) is being hosted alongside the Second Session of the Meeting of the Parties (MOP2) to the Protocol to Eliminate Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products. The plan is to discuss how to combat smoking, how to deal with the growing illicit tobacco market and how to treat new, upcoming alternatives to damaging tobacco, like vaping.

The WHO doesn’t have a great track record when it comes to public health and more in particular, when it comes to its management of the Covid-19 crisis. In sum, it has put lives at risk while also causing severe economic harm.

Despite having been warned in late December 2020 by Taiwan that a new disease had appeared in the Chinese city of Wuhan, the World Health Organisation continued to repeat China’s assurances that there was nothing much to worry about. Taiwan’s vice-president, Chen Chien-jen, pointed out that “none of the information shared by our country’s [Centers for Disease Control] is being put up” on the website of the International Health Regulations (IHR), a WHO framework for exchange of epidemic prevention and response data. French daily Le Monde revealed that China and its allies successfully lobbied the WHO to refrain from declaring a Covid-19 global emergency at its meeting of 22 and 23 January 2020. In sum, China managed not only to exclude Taiwan from the WHO but also apparently managed to involve the organization in its initial attempts to suppress information about the outbreak of Covid19. This despite the fact that China only contributes to 0.21% of the WHO’s funding.

In May 2020, Herman Goossens, a Belgian microbiologist and coordinator of the EU’s Platform for European Preparedness Against emerging Epidemics, expressed regret about the approach to follow the WHO’s recommendations, stating, “we should have looked at other countries. At Taiwan or South Korea. Countries that have kept the virus under control … Already at the beginning of January, Taiwan has put infected persons in quarantine. But it isn’t a member of the WHO and was not on our radar. In a few months, we’ll be complaining that we could have avoided this lockdown”.

Just like COP26, COP9 isn’t particularly welcoming of dissident voices, let alone stakeholders that may be able to inform the debate. In 2016, at the preceding “COP7” conference, in India, protesting tobacco farmers that were simply demanding transparency on FCTC decision-making, were rounded up and transported far away from the venue. Their calls for a boycott of the conference in Delhi received a massive outpouring of support on Twitter.

At the upcoming COP9, just like in Glasgow at COP26, industry will not be welcome. Not only tobacco farmers or manufacturers but also retailers and aligned industry are being excluded. In effect, mostly government officials will be talking to themselves, with input of NGOs to inject the messaging into the echo chamber.

In a 2018 article for Fordham International Law Journal, Gregory Jacob, who helped negotiate the FCTC while serving as an Attorney Advisor in the U.S. Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel, takes a closer look at “Secrecy and Exclusion in the FCTC Implementation Process”, truly laying bare how business is done at the WHO policy level. He notes:

“One could hardly imagine attempting to exclude unions (or business interests, for that matter) from participating in International Labour Organization (“ILO”), solely because they have an economic interest in the matters under discussion. Economic interests should of course always be transparently disclosed so that conflicts of interest can be identified and considered when crafting policy, but it is senseless for policymakers to cut themselves off entirely from useful sources of data and information.”

Thereby, he also recalls how Dr. Vera da Costa e Silva, Head of the Convention Secretariat during COP7 in Delhi called small tobacco farmers “malevolent”, with Jacob pointing out:

“Even such disfavored groups have civil rights of participation and association that are guaranteed by (among other treaties and conventions) Universal Declaration of Human Rights.”

Last but not least, he also mentions:

“For the most extreme anti-tobacco advocates, it has not been enough merely to silence impacted groups from having a voice in policy debates. These advocates have pushed for a substantially deeper level of isolation for tobacco interests, demanding (oftentimes successfully) that any government official or international organization that has contact of any kind with the tobacco industry must itself be shunned, isolated, and barred from participating in FCTC proceedings.”

Imagine the outcry if, for example Vietnam and Pakistan, some of the world’s textile manufacturing hotspots, would be banned from decision making on international labour standards. Then maybe it helps to explain why WHO seems so close to China.

It doesn’t stop there, however. In the past, even Interpol has been banned from providing input to COP on combating illicit trade in tobacco products – a subject it may know a thing or two about – apparently because it had been working with the tobacco industry to track shipments.

Another troubling issue is that – according to Jacob – the conclusions of deliberations in COP9 and the international summits preceding it “do not provide any information on which organizations or delegations were the primary drivers of the policies that were ultimately adopted, what the supporting reasons were, who expressed dissenting views, or why those views were overcome.”

Vaping

Also when it comes to the treatment of vaping, the WHO takes a hostile approach. In itself, this position can be intellectually defended, but surely, its averse stance to dissident input must play a role in adopting this particular stance. At least in certain national democracies, like the UK, there seems to be a more open debate about this. To ban everything that remotely resembles smoking may seem intellectually appealing to a child, in the real, more complex world, that may not be the best approach in order to reduce the number of tobacco users and promote public health.

The UK government is being challenged to support #Vaping at COP9 🙌

Public health authorities in the UK have embraced vaping as a viable and effective alternative to help people kick the habit.

🗞️ Read and find out more here: https://t.co/lPzjLTJ3fN#VapeNews pic.twitter.com/Dxj5BuW7jy

— Evapo (@EvapoHub) October 25, 2021

4.3 million US adult nicotine vapers are ex-smokers. https://t.co/uGXBvncE1I #FactVsMyth #Vaping #Nicotine #COP9 #Ecigarettes pic.twitter.com/aiRgdEz2MK

— Campaign for Safer Alternatives (@GoingSmokefree) November 2, 2021

That’s at least what has led to the more evidence-informed approach of the UK, which is now likely to become the first country in the world to prescribe vaping for medicinal use, as a means for smokers to quit tobacco, as a result of thorough investigation of pros and cons. Perhaps in the end, the British approach will turn out to be wrong, but at least it is the result of proper debate, not of decisions taken in a one-sided echo chamber of a shady international organization like the WHO.

Unfortunately, just as with climate policies, the EU’s approach seems to be closer to the echo chamber approach of the WHO. Its “Scientific Committee on Health, Environmental and Emerging Risks” (SCHEER) has been accused of treating evidence selectively, downplaying how vaping helps people to quite smoking. Can we say we are surprised?