By Dan Kral, Europe Economist

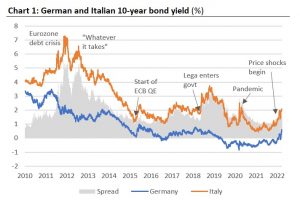

The combination of a series of negative supply-side shocks and monetary policy tightening presents a toxic mix for Eurozone governments, although we are nowhere near a re-run of the sovereign debt crisis. Yields on governments debt have risen across the bloc with the largest rises across eurozone periphery, meaning spreads with Germany have widened. The key spread between German and Italian 10-year bonds is back at around 2% and is likely to go higher, whereas it peaked at over 5% during the sovereign debt crisis. Moreover, nominal yields are still very low by historical standards. (Chart 1).

Persistence of inflation is the key factor to watch

Whether the current environment begins to present a risk for longer-term debt sustainability mainly depends on the extent to which the current inflation spike will last, in other words whether we are shifting to a new inflation regime. Permanently higher inflation would be highly problematic, as it would necessitate a much tighter policy stance by the European Central Bank, stifling demand and thus growth, and cause a re-pricing in bond markets, raising debt servicing costs for governments.

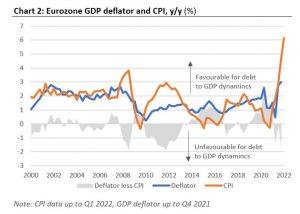

What’s further complicating the picture, high inflation does not automatically erode government debt expressed as a share of nominal GDP. This is because of the different methodologies between the consumer price index (CPI), which measures price changes faced by consumers, and which has been setting records, and the GDP deflator, which measures price changes for all actors in the economy (consumers, businesses, governments) but not importers, where increases have been more muted. In an environment where a large part of the elevated CPI is driven by soaring imported energy prices, the differential between CPI and the GDP deflator has been rising in a way that limits the favourable effects for debt dynamics (Chart 2).

The alternative scenario, whereby prices are rapidly rising across the economy (and not just a few components like energy or food) expressed in soaring GDP deflators, would require a tighter monetary policy stance, further stifling demand and raising debt servicing costs. Thus, in an imported supply-side price shock, inflating government debt away is easier said than done.

The cost-of-living squeeze puts pressure on governments to introduce measures to soften the blow for households and businesses. Unlike with the previous energy price shock in the 1970s, these have come mainly in the form of subsidizing rather than curtailing demand, which, in an environment of constrained supply, puts further upward pressure on prices (and provides a windfall for the Russian government budget). The longer the energy price squeeze continues, the wider the fiscal deficits as well as the eventual consolidation needs in an environment of tighter financial conditions.

Debt sustainability is currently not a concern

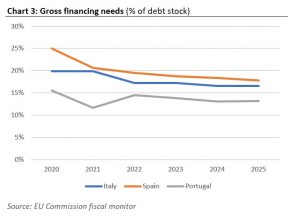

However, if the current price shock does prove to be short-lived, debt sustainability should not be endangered. After years of declining interest rates, governments have a hugely favourable starting point. The effective interest rate on Italy’s public debt declined to 2.4% in 2021 from 3.7% in 2010 (and to 1.8% from 3.2% in Spain). Given the weighted average maturity of the debt stock of around 7 years for Italy, Spain and Portugal and the expected fiscal deficits, gross financing needs are typically between 10-20% of the debt stock (Chart 3). This means that only a small share of the debt has to be (re)financed at the current higher rates, which are in any case roughly equivalent to the prevailing effective rate on government debt. Even if interest rates continue to increase, the transmission to the overall debt servicing costs will be very gradual, limiting risks for debt sustainability.

After a temporary spike in the wake of Russia's invasion of Ukraine, ZEW inflation expectations are back to signalling a drop in eurozone inflation by the end of this year. pic.twitter.com/lFFYA6av57

— Daniel Kral (@DanielKral1) May 10, 2022

Once price shocks subside, persistently high inflation in the eurozone is unlikely. More plausible is a return to the pre-pandemic norm of secular stagnation, with weak nominal growth and a tight fiscal stance, which would result in interest rates coming down, due to expected lower returns on investment and limited net supply of debt. Moreover, Next Generation EU, which has a much better chance of lifting longer-term growth potential than structural funds, given the associated conditionality, and serves as an implicit backstop by the ECB on periphery bond markets. Combined with a new OMT-like instrument signalled to the markets, this all represents an important number of EU-level support mechanisms. Government debt dynamics do not unfold in a vacuum, but are profoundly impacted by policy, which will remain supportive.

The bottom line is that unless the inflation regime would be undergoing a profound paradigm shift, public finances of European governments will be able to ride out the storm.

"The EU's Recovery Fund will not unleash a new economic bonanza across Europe"https://t.co/B91yrZXfyx

New article, by Europe economist @DanielKral1 #NGEU #RecoveryFund #EuropeanUnion— BrusselsReport.EU (@brussels_report) July 15, 2021

Disclaimer: www.BrusselsReport.eu will under no circumstance be held legally responsible or liable for the content of any article appearing on the website, as only the author of an article is legally responsible for that, also in accordance with the terms of use.