By Prof. Dr. jur. Dr. rer. pol. h.c. Carl Baudenbacher, a Partner at the law firm Nobel Baudenbacher (Zurich/Brussels) and a visiting Professor at LSE. Between 2003 and 2017, he served as the President of the EFTA Court.

6 December is St. Nicholas Day (“Samichlaus”) in Switzerland. In the evening, St. Nicholas goes from house to house and gives the good children nuts, fruit and chocolate. However, the naughty children receive a rod. (At least, that’s how it used to be.) On 6 December 1992, St. Nicholas brought a huge rod to the Swiss people and cantons. To be exact, it was the Swiss themselves who put this instrument of corporal punishment in their own house.

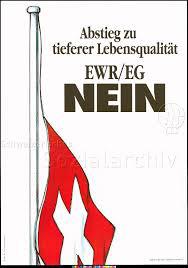

50.3% of Swiss voters and a clear majority of the cantons rejected accession to the Agreement on the European Economic Area EEA. Under this treaty, Switzerland would have adopted EU single market law and its industry would have enjoyed a privileged access to the EU’s single market. The rod is that the EU can deny Swiss operators this access at any time.

Switzerland therefore defines its relationship with Brussels bilaterally. Since 1 February 2020, however, the Alpine Republic is no longer the only Western European country that refuses multilateral integration in Europe. The United Kingdom left the EU on that day after 47 years of membership.

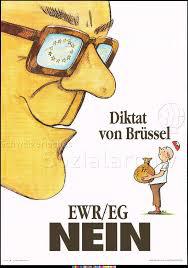

Although the export industry in particular ran a major campaign in favor of the EEA in the last few weeks before the referendum, the No vote on 6 December 1992 came as no surprise. The Federal Council, the only directorial government in the world, blamed the failure on the integration refuseniks around Christoph Blocher, a conservative member of the Grand Chamber of Parliament. They had indeed fought a tough campaign and had not always been truthful. But a (semi-) direct democracy has to put up with that. In fact, the Federal Council itself pulled the rug out from under the EEA project when it submitted an application to access the EU in May 1992. According to Federal Councillor Adolf Ogi, a former sports official, the EEA was to be the “training camp” for later EU membership. In this way, the government gave Christoph Blocher and his followers an unexpected boost. From then on they claimed that the vote of 6 December 1992 was not about joining the EEA but the EU.

Switzerland was inadequately prepared in 1989 when the preliminary talks on the creation of the EEA began. In January 1989, the legendary Commission President Jacques Delors proposed to the EFTA states an association “with common decision-making and administrative bodies”. One year later, he unceremoniously withdrew this offer which was incompatible with everything the EEC had ever advocated regarding its inviolable decision-making autonomy. While the other EFTA states nolens volens accepted this breach of promise, parts of the Swiss negotiating team elevated the “co-decision” issue in the creation of new EEA-relevant EU law to the status of the crucial question of the whole EEA. Major negotiating successes of the EFTA states, in particular the concession of a co-determination right in legislation by the EEC, the fact that the EFTA States were allowed to have their own independent surveillance authority and their own independent court of justice (so-called “institutions”) were held in low esteem. Co-decision fetishists in the negotiating delegation approached the Federal Councilors directly behind the back of Franz Blankart, the chief negotiator, who died in January 2021, and convinced a majority of them that the EEA was only acceptable for Switzerland as an interim solution on the way to EC accession.

After the EEA No, the Free Trade Agreement of 1972 with the EU remained intact and the Federal Council continued its EU accession course. It thereby achieved the willingness of the EU to conclude two packages of bilateral agreements with Switzerland, the “Bilaterals I” in 1999 and the “Bilaterals II” in 2004. These treaties provided Swiss industry with a partial (sectoral) access to the EU’s single market. They are (with one exception) characterised by the fact that they do without a supranational surveillance body and without a supranational court of justice, i.e. without institutions. Differences between the EU and Switzerland are dealt with in joint committees, which, however, can only decide by consensus. Efforts by the EU to crack down on Swiss wage protection were therefore unsuccessful. The protection of high Swiss wages when working across the border is a thorn in the side of southern German companies in particular. However, as it became increasingly clear that Switzerland’s accession to the EU was very unlikely, Brussels demanded from 2008 that the bilaterals be placed under institutions, i.e. a supranational surveillance authority and a supranational court. To this end, a “framework agreement” or “institutional agreement” was to be concluded as an umbrella over the various bilateral treaties.

At the same time, Brussels was extraordinarily generous and offered Switzerland “docking” with the EFTA Surveillance Authority (“ESA”) and the EFTA Court. “Docking” meant that Switzerland could have provided a member of the ESA College and a judge of the EFTA Court. And unlike the EEA/EFTA states Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway, it would not have had to adopt the entire single market law, but could have stuck to its sectoral approach.

Entering the EU through the back door?

The Federal Council rejected this offer in 2013 at the urging of Foreign Minister Didier Burkhalter and his State Secretary Yves Rossier. The government instead wanted to subject the bilateral agreements to monitoring by the European Commission and the jurisdiction of the Court of Justice of the EU. This attitude, which was incomprehensible in terms of sovereignty and caused even Brussels diplomats to shake their heads, can only be explained by the fact that the intention was to set a “point of no return” on the road to EU membership. The misguided decision was accompanied by an unspeakable “bullshit” campaign about the alleged functioning of surveillance and judicial control in the EU on the one hand and the EEA/EFTA on the other. “Bullshit”, according to the definition of the American moral philosopher Harry G. Frankfurt, are statements intended to persuade without regard to truth.

In 2017, Foreign Minister Burkhalter resigned because it had become clear that his Commission/ECJ model wouldn’t fly. His successor, Ignazio Cassis, promised to press the “reset button” in the EU dossier, but in the end the only innovation was that in the 2018 draft Institutional Agreement (“InstA”) an “arbitration panel” without any substantial competences was interposed before a conflict was submitted to the ECJ. This was pure “camouflage”, but the Federal Council accepted it. At first, Bern probably did not even realize where this fabulous “arbitration” model came from: from the EU’s association agreements with former post-Soviet republics. It is also envisaged for future EU trade agreements with former colonies of European powers in North Africa. After 2019, the “bullshit” campaign was continued by the new State Secretary in the Foreign Service Roberto Balzaretti.

The Federal Council nevertheless refrained from signing the InstA out of fear that it would not pass in a referendum and in May 2021 the negotiations were broken off. However, the government did not come back to the 2013 blunder on the institutions. It rather let the InstA fail on three substantive side issues (wage protection, EU citizenship directive and state aid control).

"Why did EU-Swiss negotiations on a Framework Agreement fail?"

New article, by Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. @C_Baudenbacher, President of the EFTA Court between 2003 and 2017, an independent consultant and arbitrator https://t.co/9zNFgmaGDj#InstA #EUSwiss #Switzerland @JHahnEU #efta

— BrusselsReport.EU (@brussels_report) May 27, 2021

Negotiations were continued informally. According to the Federal Council’s “Plan B”, the Commission and the ECJ are no longer to have competence under a horizontal InstA spanning the individual bilateral agreements. Instead, the jurisdiction of the non-neutral institutions of the other side is to be anchored vertically, i.e. in the individual bilateral agreements. One must assume that the hope behind this is still to lead Switzerland into the EU through the back door. Additional dossiers, e.g. in health policy, are to be added to the load. This would make it more difficult for the opponents in a referendum.

Although Switzerland has not violated any law, the Commission for its part began to use the rod that the Swiss had placed in their own house for punitive action. For example, Switzerland has been discriminatorily denied recognition of stock market equivalence – a measure that, economically speaking, is an own goal for the EU -, full admission of the Alpine republic to the Horizon 2022 research program has been blocked despite an explicit commitment to do so in 2019, and the world’s leading Helvetic MedTech industry is being harassed. With these measures, the EU is harming its own people. More “pinpricks” with regard to the privileged access to the single market are looming. This application of St. Nicholas rod is intended to bring the stubborn Swiss to heel. In fact, university presidents and representatives of the export industry demand that the dead InstA be brought back to life.

Nevertheless, the informal talks between Bern and Brussels are not getting off the ground. It is doubtful whether there will be any significant movement before the Swiss federal elections of the autumn of 2023. By 2024 at the latest, however, the government will have to make up for what it has failed to do since 1992: The individual options – in the meantime EU, EEA, “docking”, horizontal or vertical InstA, institution-free free trade – must be analysed as objectively as possible. Account must also be taken of the fact that the UK and Switzerland have important things in common with their free trade orientation, the absence of a Hegelian model of state, the liberal image of man, the strong position of judges and the leading ranks of their universities (“Britzerland”). If Bern is not in a position to make an unprejudiced assessment, civil society is called upon to do so.

Disclaimer: www.BrusselsReport.eu will under no circumstance be held legally responsible or liable for the content of any article appearing on the website, as only the author of an article is legally responsible for that, also in accordance with the terms of use.