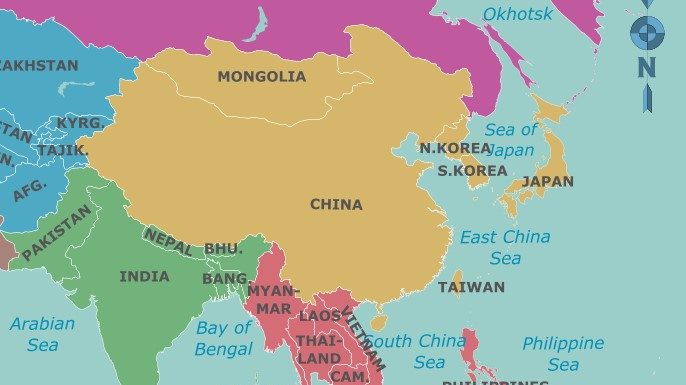

Today, EU leaders are gathering in Brussels, where they are reportedly expected to support revamping the single market and simplifying regulations, also as a response to the U.S. “Inflation Reduction Act” or IRA. Since the United States came up with these measures, more than 90 billion of supposedly “green” tax credits have been provided by the U.S., something which continues to alarm leading European companies, as both the EU and Japan are excluded from the scheme, which therefore has been deemed protectionist.

One thing of contention at the Summit is the European Commission’s proposed response to relax the EU ban on state aid, in a bid to promote a “green subsidy splurge”. Not only would this undermine fair competition within the EU – larger companies and member states tend to be more capable to catch subsidies – it would also amount to fighting protectionism with even more protectionism. EU leaders are not expected to reach a conclusion on this topic now.

A worrying thing is how the European Commission is on the side supporting watering down the ban on state aid, despite the fact that this constitutes the cornerstone of the EU single market and therefore EU cooperation. Commission President Ursula von der Leyen has even argued for a “European Sovereignty Fund”, which is yet another scheme to spend billions of euros. Thankfully, this is being opposed by her own group in the European Parliament, the European People’s Party. Portugese EPP MEP Maria da Graça Carvalho has pointed out that “We have plenty of funds that are not used at the moment”, for example from the EU’s Covid recovery fund. It all raises ever more question marks over the wisdom of appointing von der Leyen.

🇪🇺European Union leaders are expected on Thursday to back a revamp of the single market, simplified regulations and other steps to ensure the bloc can compete with the🇺🇸United States and🇨🇳China as an industrial leader in green and digital technologies.https://t.co/fVAePrT3EL

— Francesco Sassi (@Frank_Stones) March 23, 2023

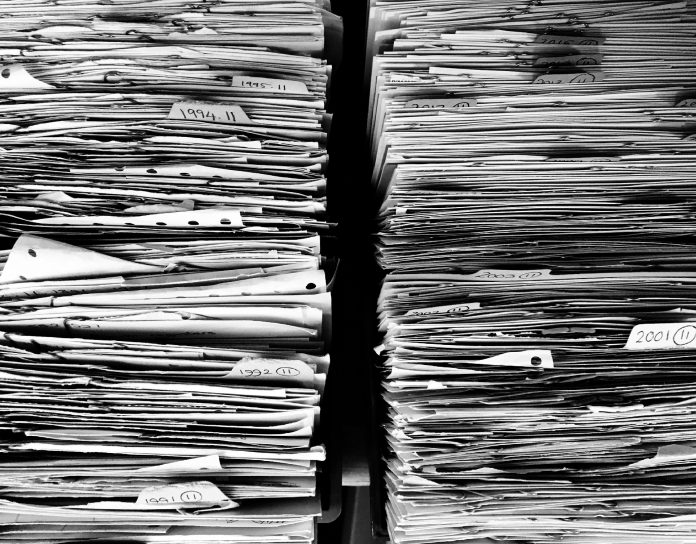

The ever increasing cost of EU regulation

Even if some major companies would like to see more EU cash injections, sensible criticism has also come from industry. Belén Garijo, the ceo of German biotech and materials giant Merck, thinks Europe “urgently needs a holistic industrial policy that enables sustainable change and makes this change a competitive advantage» About the “net zero Industry Act», he thinks this simply «does not solve these issues”, adding that if Europe was serious about competitiveness, it needs to “start cutting red tape . . . Enabling competitiveness requires a fundamental shift in policy to attract and retain highly innovative industries.”

In the past, large-scale research by my former think tank, Open Europe, concluded that the cumulative cost of EU regulation introduced between 1998 and 2008 for all 27 EU member states is €928 billion, which is 66% of the €1.4 trillion which all national and EU regulation introduced during that period has costed. Today, the cost of EU regulation remains a massive challenge. The German Regulatory Control Council estimates that during the pandemic, EU law has added an annual compliance burden of €550mn on companies. BusinessEurope, the federation of European businesses, has conducted an international survey in 35 countries among global firms, concluding that 90 percent of them believe that the European Union has become a less attractive place to invest than three years ago. They therefore blame high energy prices – still not sorted – and increased regulation.

Climate zealotry

Before 2019, Frans Timmermans, the current EU “climate” Commissioner, was responsible for “better regulation”, but these days seem long over. Instead, Timmermans has become the face of the European Commission’s never ending climate zealotry, which aims to expand the EU’s emission trading scheme into ever more economic sectors and – to compensate for the EU burdens imposed on domestic companies – also burden imports into Europe with a climate tariff, something which will ultimately hit the end consumer.

The latest EU initiative in a long row of proposals to impose extra reductions on doing business in Europe is the “Net Zero Industry Act”, whereby it wants to set a goal to produce at least 40% of the technology for climate and energy targets by 2030 at home, in the European Union. At least it is only a political objective and not a legal requirement, but it comes with all kinds of support schemes, whereby also nuclear energy will be discriminated against – despite the fact that this energy source has a zero carbon footprint. The European Commission thereby ignores its obligations under the Euratom Treaty, which requires the signatories to promote nuclear power.

This is all yet more evidence of green policies degrading into central planning and protectionism. Francisco Beirão, head of EU government affairs at Lightsource bp, which develops and manages solar projects, calls the EU’s latest proposal, taken in fear of competition from the U.S. and China “very protectionist”, as it could force solar developers to use more expensive products.

With 🇪🇺 leaders today and tomorrow – for once! – having also the issue of competitiveness on their agenda, they must be aware of the risk of falling into “crude protectionism and dirigisme” as proposed in some quarters. https://t.co/FFbV2SkyPu

— Carl Bildt (@carlbildt) March 23, 2023

A divergent UK

Meanwhile, the United Kingdom has opted for a different path. Yes, the UK has hardly scrapped any of the EU regulations it has automatically transposed into UK law – scrapping legislation tends to wake up all kinds of vested interests – but when it comes to dealing with new challenges, the British could teach the EU a thing or two.

One example is how the UK will eliminate its tariffs on Malaysian palm oil, which should also allow it to enter the “Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership”, one of the world’s largest free-trade areas by GDP. Originally, the U.S. were supposed to be part of it, when it was called “Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP)”, but then U.S. President Donald Trump decided to withdraw in 2016. The UK managing to join this arrangement can be considered the UK’s first post Brexit trade success.

The contrast with the European Union is striking. While the UK simply provides to accept the regulation of its trading partners when it comes to palm oil, the European Union has adopted a habit of attempting to impose its regulatory choices on trading partners. This has angered some of them, including Malaysia and Indonesia, and this certainly is one of the reasons why the EU has lately failed to achieve much success in closing trade deals with South East Asia. Even ratifying trade deals that have been concluded, like the EU-Mercosur deal, is suffering lots of domestic opposition in the EU, not only from the usual protectionist suspects, like France, but also from Ireland, the Netherlands and Austria.

Often, the EU’s arguments to justify imposing its own regulatory choices, are also nothing more than veiled protectionism, and this certainly is the case with palm oil. The EU has been hammering the typical South East Asian import product with regulations like the renewable energy directive and the new EU deforestation regulation. However, as also the WWF has pointed out, “compared to other vegetable oils the oil palm is a very efficient crop, able to produce high quantities of oil over small areas of land, almost all year round.” To replace them with alternatives like soya bean, coconut or sunflower is estimated to require between four and ten times as much land, something which would cause damage to the environment elsewhere.

Countries like Malaysia have schemes in place to certify sustainable palm oil production. Malaysia’s Sime Darby, the world’s largest producer of certified sustainable palm oil, has for example pledged to reforest a 400-hectare area of peat plantations in the provinces Sabah and Sarawak, this as part of its commitment to net-zero by 2050 in order to achieve a more sustainable future. Earlier this year, US Customs also decided to grant the company a clean bill of health, which allows it to resume imports of palm oil into the US, after a two-year import ban on these products.

Closet protectionism

Despite all that, the EU prefers – unlike the UK – to impose its own, burdensome and detailed compliance requirements, something which South East Asian nations simply consider to be protectionism, and why they have dragged the EU before the WTO. The EU may well lose, given how in a related case, a WTO panel already condemned the EU for imposing antidumping duties on Indonesian biodiesel.

At least according to the Financial Times, the rumours are that European oilseeds producers would be behind much of these supposedly “green” EU measures. Is anyone surprised?