By Dr. Susanna Lukacs

75 years after its adoption, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, namely article 17, is under threat.

It states:

“Everyone has the right to own property alone as well as in association with others. No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his or her property.”

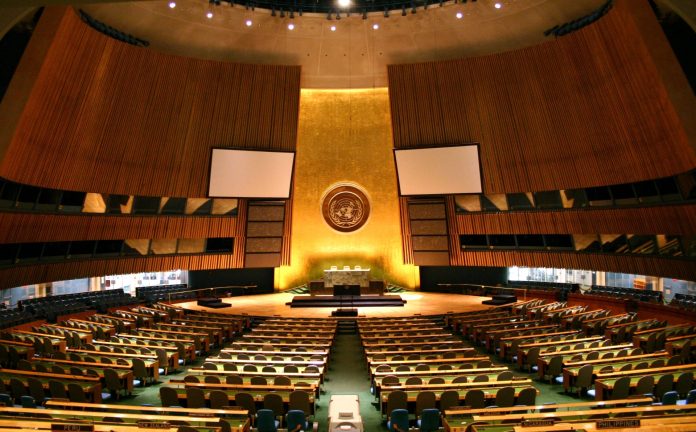

On December 10, 1948, the UN accepted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). The Declaration is considered a “milestone document” inspiring the development of international human rights. But article 17 of the UDHR that guarantees the right to property is currently being undermined, as many are arguing it leads to economic inequality. Much of “mainstream human rights thinking is undercutting private property ownership as a human right in the sense of setting up safeguards against expropriation.” In fact, as of late, redistributive land policies for inclusive growth and poverty eradication propagated by the United Nations, seek to implement redistributive land policies, transferring land from the rich to the landless to alleviate poverty.

The study, “Redistributive Land Policies for Inclusive Growth and Poverty Eradication” commissioned by the UN, distinctly states that redistributive land policies seek to “directly transfer land from the land-rich to the landless and land-poor” to alleviate poverty and inequality while “simultaneously appeasing the possibility of political threats or revolts among the rural poor and peasantry” is one of the many solutions to limiting poverty.

It is further highlighted that in the current global context, land redistribution that protects land access for the “most vulnerable and marginalized people and promotes equitable and democratic redistributive reforms […] must be designed and implemented with an explicit pro-poor bias in order to ensure the most marginalized and vulnerable benefit – with the aim to ‘leave no one behind’ and ‘reach the furthest behind first.” The method proposed by the study clearly does not honour article 17 of the UDHR, blatantly subverting one’s right to own and safeguard one’s property.

Philip Alston, Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty for the UN has gone as far as having criticised several states for the privatisation of “public goods,” claiming it is an “overlooked” human rights problem, urging authorities to challenge privatisation. The Special Rapporteur attributes privatisation to “neoliberal economic policies” aiming to “shrink the role of the State.” Oddly, property rights are no longer considered just, nor do they play a role in human rights discourse.

Mr. Alston’s negative view of privatisation certainly struck a chord with South Africa’s Expropriation Act. Local, provincial, and national authorities could implement this legislation to expropriate land in the public interest, for “land reform” and measures that bring about equitable access to South Africa’s natural resources. In 2021, a proposed amendment to Section 25 to the South African Constitution was as an outright threat to article 17 of the UDHR, allowing for the expropriation of land without compensation. “On December 7th, 2021 the bill flopped, South Africa`s majority ruling political party failed to secure the two-thirds of parliamentary votes required to pass the amendment.” The proposed legitimisation of land expropriation without compensation is a cautionary tale.

South Africa's large population and strong industry make it an important Sub-Saharan nation.

🚨 However, @PhumlaniMMajozi explains that the 'expropriation without compensation' act is making many people worried about the country's future…😟 https://t.co/vpGv2UwjDj pic.twitter.com/4dwmf7NAM0

— Initiative For African Trade and Prosperity (@the_iatp) May 15, 2023

Human rights acknowledge the essence of property rights

It is worthwhile to recall the history that inspired article 17, to put the issue into perspective. The Magna Carta Libertatum (The Greater Charter of Freedoms) of 1215 was first drafted by the Archbishop of Canterbury, Cardinal Stephen Langton, claiming individual freedoms cannot be limited by the monarch: no Englishman could be “arrested, imprisoned or disseised [have property confiscated, outlawed, exiled, or in any other way ruined […] except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land.” Jurist Sir Edward Coke drew on the Magna Carta in the 17th century questioning the divine rights of the monarch and upholding judicial authority in safeguarding the rights of individuals to freedom and property. The royal charter influenced the formation of the United States Constitution as regards property rights protection, disallowing unlawful expropriation.

The Virginia Declaration of Rights (1776) which foreshadowed the U.S. Bill of Rights and the Fifth Amendment of the American Constitution, namely Article One declares property possession as an inherent right of all men. James Madison in 1792, similarly, highlighted the guiding principle that “Government is instituted to protect property of every sort; as well that which lies in the various rights of individuals, as that which the term particularly expresses.”

The founding fathers of America and the early European advocates of liberal democracy understood the sanctity of property rights and other freedoms, they are of utmost importance and should be revisited to safeguard its protection.

excited for release of @PRAlliance International Property Rights Index #IPRI2023

in which I contributed with a case study on the #propertyregistration in #Egypt " the ballad of property registration in Egypt"

thanks @lorenzmontanari @saryle @HDeSotoPeru #libertyinmotion… pic.twitter.com/sGHreosFzu— Mohamed M. Farid (@Mohamed_M_Farid) September 27, 2023

Developing countries need better policy making

Land redistribution and land expropriation without compensation is not the solution. According to a World Bank study, intact property rights and land registration are the pillars of a modern economy. Secure property rights and access to land are crucial for business development and labour: “The private sector needs land to build factories, commercial buildings, and residential properties.” A report evaluating private sector outcomes in the Middle East and North Africa concludes that the “top constraints to the region’s private sector include the lack of access to land as well as issues related to land titling and registration.” Companies often use land or property titles as “collateral to finance operational costs as well as to expand existing businesses or open new ones, thus creating more jobs”. “Countries in the top 10 of the IPRI are developed countries with a high GDP per capita, enjoying higher incomes than the countries with lower scores.”

Developed countries that operate a welfare state should help developing countries implement the legal and administrative know-how necessary for making property rights effective in reducing poverty. Such measures have recently been initiated by the Swedish government. The new strategy published in the summer of 2022 entitled “Strategy for Sweden’s development cooperation in research for poverty reduction and sustainable development 2022– 2028” envisages Sweden’s international development assistance in creating “conditions that improve the lives of people living in poverty and oppression.” The strategy’s enhanced research analyses “poverty reduction and sustainable development through mutually supportive initiatives.” Sweden has extensive experience in “development cooperation” on poverty reduction, and sustainable development. Such research activities will contribute to policy development, effective “decisions,” applications, and “innovations.”

Chris Butler, Executive Director of Tholos Foundation, presenting the International Property Rights Index, which correlates with quite a few other metrics (GDP, economic freedom etc)https://t.co/rXwaRuXVvY. pic.twitter.com/8zkxzozkn9

— BrusselsReport.EU (@brussels_report) May 10, 2022

The Nordic model

The Nordic welfare model is often hailed in the international debate. Poverty in the region is at a minimum. “Finland’s IPRI score ranks first in the world IPRI, Norway and Denmark rank 4th.” Few other countries in the world can pride themselves on a well-run safety net with an emphasis on “strong property rights protection, monetary freedom, and free trade.”

The mixed economic system of the Nordic countries safeguards private property while allowing property owners the freedom to make decisions on resource utilisation. Also, the idea of equal opportunities is pervasive and in practice, it has resulted in the reduction of economic inequality. Replicating this model in developing countries could lead to solutions concerning democracy, human rights, and gender equality, including the need for enhanced research initiatives in the areas of sustainability.

Disclaimer: www.BrusselsReport.eu will under no circumstance be held legally responsible or liable for the content of any article appearing on the website, as only the author of an article is legally responsible for that, also in accordance with the terms of use.