A closer look at the EU’s new murky joint borrowing schemes

Last Friday, the German Constitutional Court ruled to suspend the German law ratifying the EU’s €750 billion “recovery fund”. This caused quite a stir. It’s a reminder of what economist Daniel Kral stressed on BrusselsReport.eu: that legal challenges will continue to pose a risk for any Eurozone transfers.

At least the Financial Times seems to have lost its cool. An editorial argued that “the best hope might be a changing of the guard on the court itself”, while describing proper legal scrutiny of mass EU borrowing as “doctrinal thinking”.

We can already guess what the governments of Poland and Hungary will respond the next time the FT highlights their rule of law deficiencies.

The idea that Eurozone transfers are badly needed is something of a “no brainer” among the “financial crowd” – investors, bankers and financial analysts. As they say, “it is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it”, and certainly if that man is working in an industry desperate for ever more debt.

Many finances types genuinely do not see the problem, even in the face of the evidence that all the cheap money unleashed by the ECB in the last ten years, meant to provide some breathing room for Eurozone governments to finally implement structural reforms, has mainly done the opposite.

In a damning 2019 paper, German think tank CEP concluded that:

“Although Mario Draghi was able to reassure the capital market players with this promise, it did nothing to change the fundamental problems of the eurozone. In particular, the problem of the divergent competitiveness of the Eurozone countries remains unsolved.”

The EU’s “recovery fund” is simply yet another attempt to refuel the European economies with the help of transfers, even if now, also non-Eurozone countries will profit from it, which is very worrying, given how sensitive to corruption some of their national administrations are.

Certain conditions to receive the cash will be attached, but from experience, it should be questioned how much of a positive role this will play – never mind the accompanying loss of democratic control. Dutch Professor Adriaan Schout made a good point in NRC Handelsblad last week, when he urged the Netherlands “not to make use of the EU Corona fund”, arguing that “it is questionable that the European Commission attaches strings for the Netherlands”, adding that just like with the IMF, this kind of support should only go to countries in need and only them should have to accept conditionality.

In any case, according to the European Commission, not a single EU member state has already submitted the final version of the “national recovery plan” to unlock the recovery funds.

The first signs were not exactly inspiring confidence. In December, it appeared that the Italian government was planning to spend 74.3 billion euro from the 209 billion euro it gets from the EU’s “recovery fund” at “ecological transition” and 17.1 billion euro at “gender equality”. Let’s see how different the approach by the new government, led by Mr. Draghi, will be.

A key aspect of the “recovery fund” is that is funded by loans jointly issued by EU member states. This has been dubbed “Europe’s Hamiltonian moment”, seemingly ignoring Hamilton wasn’t all that great.

Supposedly, the scheme will be “temporary” and member states will pay back the loans with EU taxes, something enabled by the legislation which EU member states are currently ratifying. At least 11 EU member states would still need to ratify the EU’s “Own Resources Decision”, which increases the EU budgetary ceiling to borrow those funds. The Commission is confident that by July, this will be completed.

The EU has been engaged in joint borrowing schemes before – amongst others with the temporary Eurozone bailout fund EFSM – but an important reason why this time it may not be temporary is that it will be very tempting for EU governments to avoid paying back the loans and simply have another round of joint EU borrowing instead, in order to finance the old loans. After all, taking out a new loan in order to pay for an old one is standard national government procedure.

The problem here is that this ultimately erodes the creditworthiness of the economies actually guaranteeing to investors that the loans will be paid back, Germany in the first place.

Sure, theoretically, funds could be raised that could then be wisely invested by economically weaker EU member states, enabling them to outgrow their debt levels, but during the last 10 years, we’ve been able to witness how well this theory holds up in practice with Eurozone governments simply squandering the opportunity cheap ECB funding provided to implement structural reforms that can then generate growth – never mind the dismal track record of EU regional transfers.

A legal analysis by German Constitutional scholar Benedikt Riedl takes a closer look at the case against the German ratification law, thereby listing a whole range of issues that may cause the legislation to be deemed unconstitutional, amongst others the “lack of transparency when it comes to the procurement of the means…Which institutions will issue these loans? Has the European Commission got the free hand in all of this?”

These are incredibly important questions (primarily related to German law, irrespective of whether the new EU initiative violates EU law), certainly considering the risk that this scheme may become permanent.

The particular question of who would be actually lending the money to the EU also applies to another scheme involving joint EU borrowing, called “Support to mitigate Unemployment Risks in an Emergency” (SURE), amounting to €100 billion euro. For this, the EU Commission has already borrowed on the markets, and EU Commission President von der Leyen now goes around boasting how the EU has been lending some of this cash to Italy, Belgium, Cyprus, Greece, Malta and others.

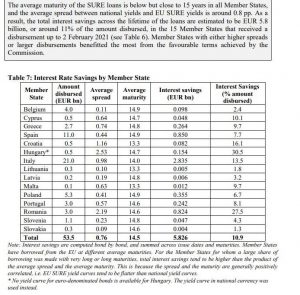

In this regard, the European Commission also published a table, detailing how much member states have saved in interest rate payments. Italy emerges as a big winner, having saved almost 3 billion euro in interests, as compared with the situation whereby it would have to borrow the SURE funds on the markets itself.

Absent from this list: Germany, the Netherlands, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Austria, France, Ireland and other states that are ultimately serving as the guarantors of these joint EU borrowing exercises.

Also here, there is no transparency on who those new creditors to the EU now are. China? The ECB – which already is the largest creditor to Eurozone democracies – ? Private investors?

Shouldn’t this be something EU citizens know when they are being burdened with billions of euros of extra debt through new, rather murky EU schemes?